As seen on https://huggingface.co/blog/assisted-generation

title: "Assisted Generation: a new direction toward low-latency text generation" thumbnail: /blog/assets/assisted-generation/thumbnail.png authors: - user: joaogante

Assisted Generation: a new direction toward low-latency text generation

Large language models are all the rage these days, with many companies investing significant resources to scale them up and unlock new capabilities. However, as humans with ever-decreasing attention spans, we also dislike their slow response times. Latency is critical for a good user experience, and smaller models are often used despite their lower quality (e.g. in code completion).

Why is text generation so slow? What’s preventing you from deploying low-latency large language models without going bankrupt? In this blog post, we will revisit the bottlenecks for autoregressive text generation and introduce a new decoding method to tackle the latency problem. You’ll see that by using our new method, assisted generation, you can reduce latency up to 10x in commodity hardware!

Understanding text generation latency

The core of modern text generation is straightforward to understand. Let’s look at the central piece, the ML model. Its input contains a text sequence, which includes the text generated so far, and potentially other model-specific components (for instance, Whisper also has an audio input). The model takes the input and runs a forward pass: the input is fed to the model and passed sequentially along its layers until the unnormalized log probabilities for the next token are predicted (also known as logits). A token may consist of entire words, sub-words, or even individual characters, depending on the model. The illustrated GPT-2 is a great reference if you’d like to dive deeper into this part of text generation.

A model forward pass gets you the logits for the next token, which you can freely manipulate (e.g. set the probability of undesirable words or sequences to 0). The following step in text generation is to select the next token from these logits. Common strategies include picking the most likely token, known as greedy decoding, or sampling from their distribution, also called multinomial sampling. Chaining model forward passes with next token selection iteratively gets you text generation. This explanation is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to decoding methods; please refer to our blog post on text generation for an in-depth exploration.

From the description above, the latency bottleneck in text generation is clear: running a model forward pass for large models is slow, and you may need to do hundreds of them in a sequence. But let’s dive deeper: why are forward passes slow? Forward passes are typically dominated by matrix multiplications and, after a quick visit to the corresponding wikipedia section, you can tell that memory bandwidth is the limitation in this operation (e.g. from the GPU RAM to the GPU compute cores). In other words, the bottleneck in the forward pass comes from loading the model layer weights into the computation cores of your device, not from performing the computations themselves.

At the moment, you have three main avenues you can explore to get the most out of text generation, all tackling the performance of the model forward pass. First, you have the hardware-specific model optimizations. For instance, your device may be compatible with Flash Attention, which speeds up the attention layer through a reorder of the operations, or INT8 quantization, which reduces the size of the model weights.

Second, when you know you’ll get concurrent text generation requests, you can batch the inputs and massively increase the throughput with a small latency penalty. The model layer weights loaded into the device are now used on several input rows in parallel, which means that you’ll get more tokens out for approximately the same memory bandwidth burden. The catch with batching is that you need additional device memory (or to offload the memory somewhere) – at the end of this spectrum, you can see projects like FlexGen which optimize throughput at the expense of latency.

# Example showcasing the impact of batched generation. Measurement device: RTX3090

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer

import time

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("distilgpt2").to("cuda")

inputs = tokenizer(["Hello world"], return_tensors="pt").to("cuda")

def print_tokens_per_second(batch_size):

new_tokens = 100

cumulative_time = 0

# warmup

model.generate(

**inputs, do_sample=True, max_new_tokens=new_tokens, num_return_sequences=batch_size

)

for _ in range(10):

start = time.time()

model.generate(

**inputs, do_sample=True, max_new_tokens=new_tokens, num_return_sequences=batch_size

)

cumulative_time += time.time() - start

print(f"Tokens per second: {new_tokens * batch_size * 10 / cumulative_time:.1f}")

print_tokens_per_second(1) # Tokens per second: 418.3

print_tokens_per_second(64) # Tokens per second: 16266.2 (~39x more tokens per second)

Finally, if you have multiple devices available to you, you can distribute the workload using Tensor Parallelism and obtain lower latency. With Tensor Parallelism, you split the memory bandwidth burden across multiple devices, but you now have to consider inter-device communication bottlenecks in addition to the monetary cost of running multiple devices. The benefits depend largely on the model size: models that easily fit on a single consumer device see very limited benefits. Taking the results from this DeepSpeed blog post, you see that you can spread a 17B parameter model across 4 GPUs to reduce the latency by 1.5x (Figure 7).

These three types of improvements can be used in tandem, resulting in high throughput solutions. However, after applying hardware-specific optimizations, there are limited options to reduce latency – and the existing options are expensive. Let’s fix that!

Language decoder forward pass, revisited

You’ve read above that each model forward pass yields the logits for the next token, but that’s actually an incomplete description. During text generation, the typical iteration consists in the model receiving as input the latest generated token, plus cached internal computations for all other previous inputs, returning the next token logits. Caching is used to avoid redundant computations, resulting in faster forward passes, but it’s not mandatory (and can be used partially). When caching is disabled, the input contains the entire sequence of tokens generated so far and the output contains the logits corresponding to the next token for all positions in the sequence! The logits at position N correspond to the distribution for the next token if the input consisted of the first N tokens, ignoring all subsequent tokens in the sequence. In the particular case of greedy decoding, if you pass the generated sequence as input and apply the argmax operator to the resulting logits, you will obtain the generated sequence back.

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer

tok = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

inputs = tok(["The"], return_tensors="pt")

generated = model.generate(**inputs, do_sample=False, max_new_tokens=10)

forward_confirmation = model(generated).logits.argmax(-1)

# We exclude the opposing tips from each sequence: the forward pass returns

# the logits for the next token, so it is shifted by one position.

print(generated[:-1].tolist() == forward_confirmation[1:].tolist()) # True

This means that you can use a model forward pass for a different purpose: in addition to feeding some tokens to predict the next one, you can also pass a sequence to the model and double-check whether the model would generate that same sequence (or part of it).

Let’s consider for a second that you have access to a magical latency-free oracle model that generates the same sequence as your model, for any given input. For argument’s sake, it can’t be used directly, it’s limited to being an assistant to your generation procedure. Using the property described above, you could use this assistant model to get candidate output tokens followed by a forward pass with your model to confirm that they are indeed correct. In this utopian scenario, the latency of text generation would be reduced from O(n) to O(1), with n being the number of generated tokens. For long generations, we're talking about several orders of magnitude.

Walking a step towards reality, let's assume the assistant model has lost its oracle properties. Now it’s a latency-free model that gets some of the candidate tokens wrong, according to your model. Due to the autoregressive nature of the task, as soon as the assistant gets a token wrong, all subsequent candidates must be invalidated. However, that does not prevent you from querying the assistant again, after correcting the wrong token with your model, and repeating this process iteratively. Even if the assistant fails a few tokens, text generation would have an order of magnitude less latency than in its original form.

Obviously, there are no latency-free assistant models. Nevertheless, it is relatively easy to find a model that approximates some other model’s text generation outputs – smaller versions of the same architecture trained similarly often fit this property. Moreover, when the difference in model sizes becomes significant, the cost of using the smaller model as an assistant becomes an afterthought after factoring in the benefits of skipping a few forward passes! You now understand the core of assisted generation.

Greedy decoding with assisted generation

Assisted generation is a balancing act. You want the assistant to quickly generate a candidate sequence while being as accurate as possible. If the assistant has poor quality, your get the cost of using the assistant model with little to no benefits. On the other hand, optimizing the quality of the candidate sequences may imply the use of slow assistants, resulting in a net slowdown. While we can't automate the selection of the assistant model for you, we’ve included an additional requirement and a heuristic to ensure the time spent with the assistant stays in check.

First, the requirement – the assistant must have the exact same tokenizer as your model. If this requirement was not in place, expensive token decoding and re-encoding steps would have to be added. Furthermore, these additional steps would have to happen on the CPU, which in turn may need slow inter-device data transfers. Fast usage of the assistant is critical for the benefits of assisted generation to show up.

Finally, the heuristic. By this point, you have probably noticed the similarities between the movie Inception and assisted generation – you are, after all, running text generation inside text generation. There will be one assistant model forward pass per candidate token, and we know that forward passes are expensive. While you can’t know in advance the number of tokens that the assistant model will get right, you can keep track of this information and use it to limit the number of candidate tokens requested to the assistant – some sections of the output are easier to anticipate than others.

Wrapping all up, here’s our original implementation of the assisted generation loop (code):

- Use greedy decoding to generate a certain number of candidate tokens with the assistant model, producing

candidates. The number of produced candidate tokens is initialized to5the first time assisted generation is called. - Using our model, do a forward pass with

candidates, obtaininglogits. - Use the token selection method (

.argmax()for greedy search or.multinomial()for sampling) to get thenext_tokensfromlogits. - Compare

next_tokenstocandidatesand get the number of matching tokens. Remember that this comparison has to be done with left-to-right causality: after the first mismatch, all candidates are invalidated. - Use the number of matches to slice things up and discard variables related to unconfirmed candidate tokens. In essence, in

next_tokens, keep the matching tokens plus the first divergent token (which our model generates from a valid candidate subsequence). - Adjust the number of candidate tokens to be produced in the next iteration — our original heuristic increases it by

2if ALL tokens match and decreases it by1otherwise.

We’ve designed the API in 🤗 Transformers such that this process is hassle-free for you. All you need to do is to pass the assistant model under the new assistant_model keyword argument and reap the latency gains! At the time of the release of this blog post, assisted generation is limited to a batch size of 1.

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer

import torch

prompt = "Alice and Bob"

checkpoint = "EleutherAI/pythia-1.4b-deduped"

assistant_checkpoint = "EleutherAI/pythia-160m-deduped"

device = "cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu"

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(checkpoint)

inputs = tokenizer(prompt, return_tensors="pt").to(device)

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(checkpoint).to(device)

assistant_model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(assistant_checkpoint).to(device)

outputs = model.generate(**inputs, assistant_model=assistant_model)

print(tokenizer.batch_decode(outputs, skip_special_tokens=True))

# ['Alice and Bob are sitting in a bar. Alice is drinking a beer and Bob is drinking a']

Is the additional internal complexity worth it? Let’s have a look at the latency numbers for the greedy decoding case (results for sampling are in the next section), considering a batch size of 1. These results were pulled directly out of 🤗 Transformers without any additional optimizations, so you should be able to reproduce them in your setup.

Glancing at the collected numbers, we see that assisted generation can deliver significant latency reductions in diverse settings, but it is not a silver bullet – you should benchmark it before applying it to your use case. We can conclude that assisted generation:

- 🤏 Requires access to an assistant model that is at least an order of magnitude smaller than your model (the bigger the difference, the better);

- 🚀 Gets up to 3x speedups in the presence of INT8 and up to 2x otherwise, when the model fits in the GPU memory;

- 🤯 If you’re playing with models that do not fit in your GPU and are relying on memory offloading, you can see up to 10x speedups;

- 📄 Shines in input-grounded tasks, like automatic speech recognition or summarization.

Sample with assisted generation

Greedy decoding is suited for input-grounded tasks (automatic speech recognition, translation, summarization, ...) or factual knowledge-seeking. Open-ended tasks requiring large levels of creativity, such as most uses of a language model as a chatbot, should use sampling instead. Assisted generation is naturally designed for greedy decoding, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t use assisted generation with multinomial sampling!

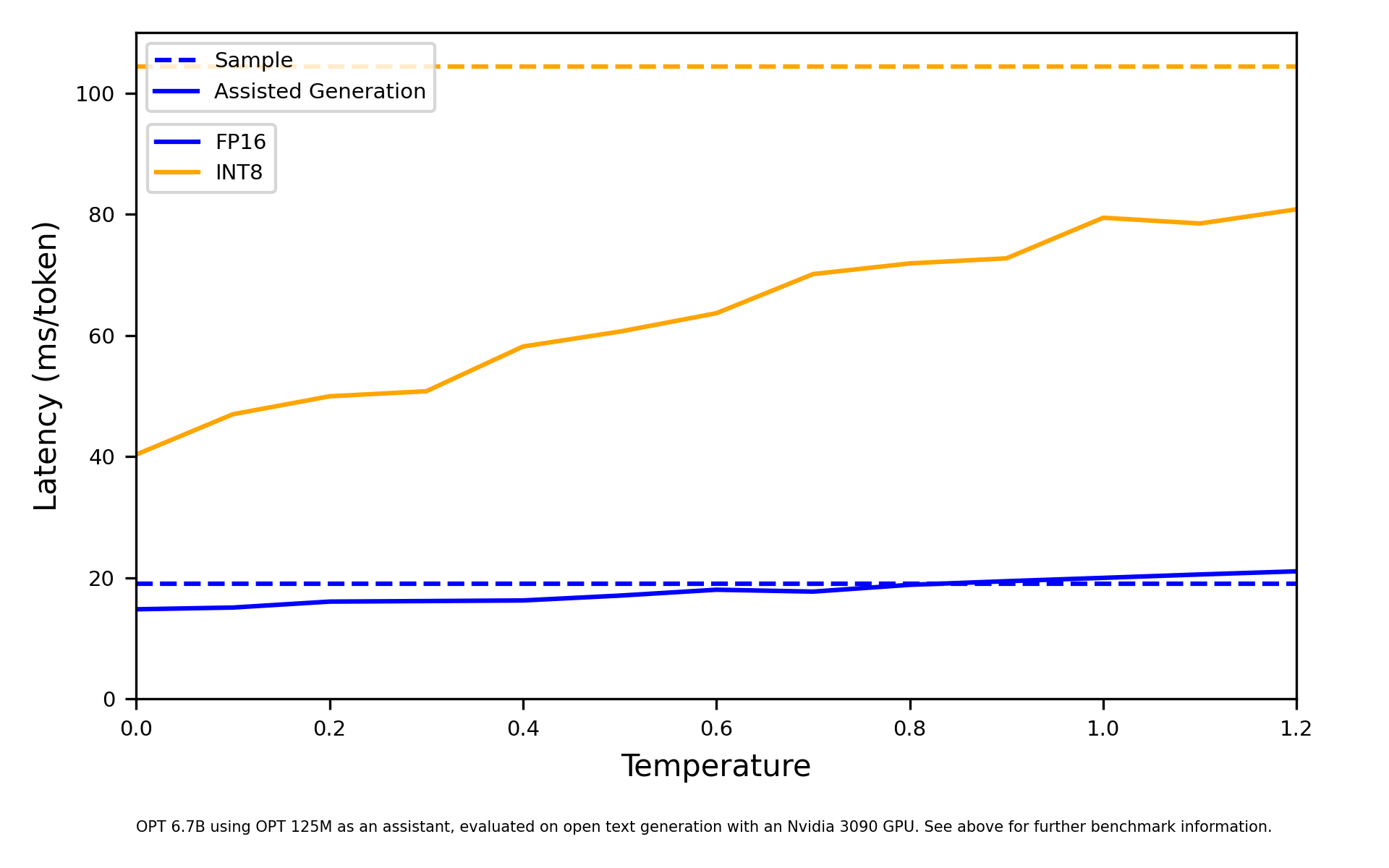

Drawing samples from a probability distribution for the next token will cause our greedy assistant to fail more often, reducing its latency benefits. However, we can control how sharp the probability distribution for the next tokens is, using the temperature coefficient that’s present in most sampling-based applications. At one extreme, with temperatures close to 0, sampling will approximate greedy decoding, favoring the most likely token. At the other extreme, with the temperature set to values much larger than 1, sampling will be chaotic, drawing from a uniform distribution. Low temperatures are, therefore, more favorable to your assistant model, retaining most of the latency benefits from assisted generation, as we can see below.

Why don't you see it for yourself, so get a feeling of assisted generation?

Future directions

Assisted generation shows that modern text generation strategies are ripe for optimization. Understanding that it is currently a memory-bound problem, not a compute-bound problem, allows us to apply simple heuristics to get the most out of the available memory bandwidth, alleviating the bottleneck. We believe that further refinement of the use of assistant models will get us even bigger latency reductions - for instance, we may be able to skip a few more forward passes if we request the assistant to generate several candidate continuations. Naturally, releasing high-quality small models to be used as assistants will be critical to realizing and amplifying the benefits.

Initially released under our 🤗 Transformers library, to be used with the .generate() function, we expect to offer it throughout the Hugging Face universe. Its implementation is also completely open-source so, if you’re working on text generation and not using our tools, feel free to use it as a reference.

Finally, assisted generation resurfaces a crucial question in text generation. The field has been evolving with the constraint where all new tokens are the result of a fixed amount of compute, for a given model. One token per homogeneous forward pass, in pure autoregressive fashion. This blog post reinforces the idea that it shouldn’t be the case: large subsections of the generated output can also be equally generated by models that are a fraction of the size. For that, we’ll need new model architectures and decoding methods – we’re excited to see what the future holds!

Related Work

After the original release of this blog post, it came to my attention that other works have explored the same core principle (use a forward pass to validate longer continuations). In particular, have a look at the following works:

- Blockwise Parallel Decoding, by Google Brain

- Speculative Sampling, by DeepMind

Citation

@misc {gante2023assisted,

author = { {Joao Gante} },

title = { Assisted Generation: a new direction toward low-latency text generation },

year = 2023,

url = { https://huggingface.co/blog/assisted-generation },

doi = { 10.57967/hf/0638 },

publisher = { Hugging Face Blog }

}

Acknowledgements

I'd like to thank Sylvain Gugger, Nicolas Patry, and Lewis Tunstall for sharing many valuable suggestions to improve this blog post. Finally, kudos to Chunte Lee for designing the gorgeous cover you can see in our web page.