url

stringlengths 67

81

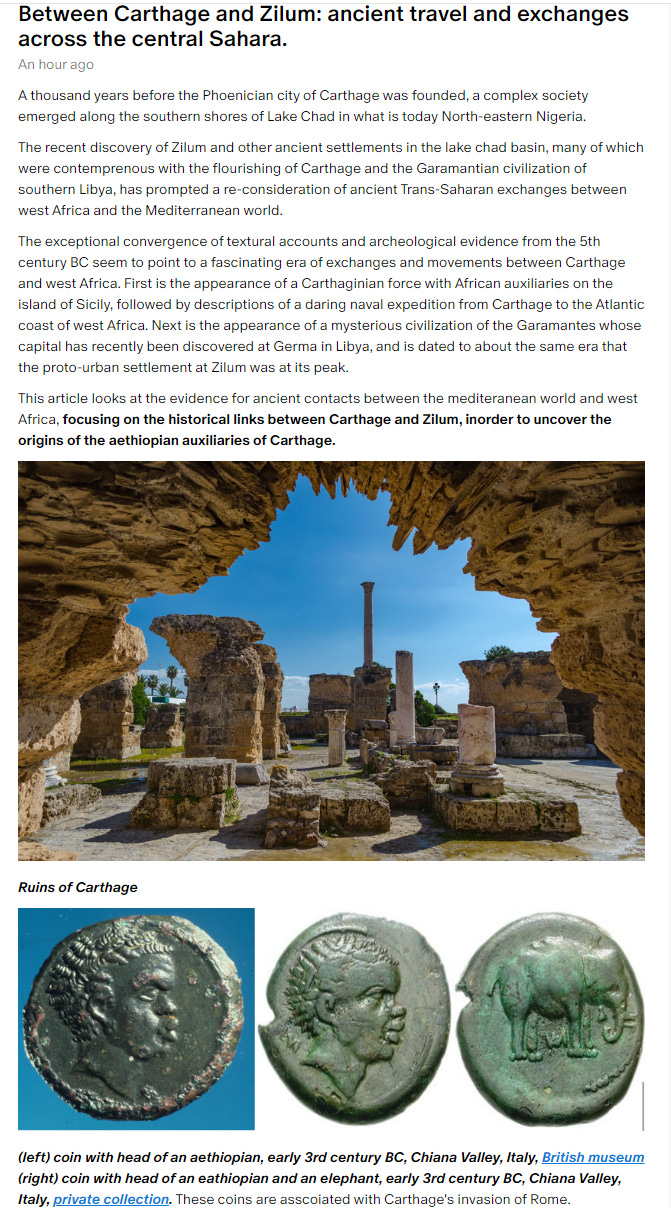

| markdown_content

stringlengths 4.76k

95.5k

| image_urls

listlengths 3

84

|

|---|---|---|

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-indegenous-versus-foreign-origins

|

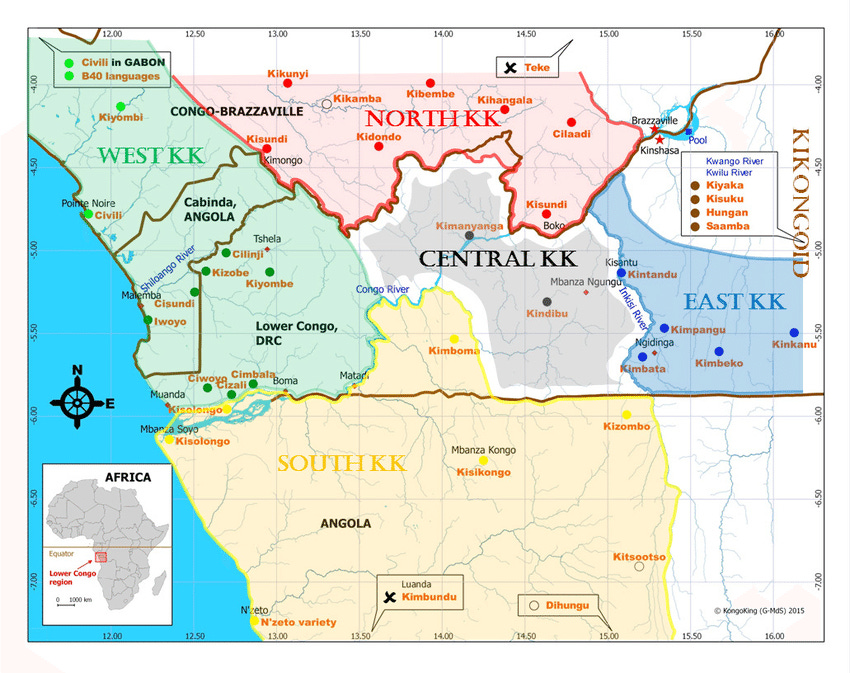

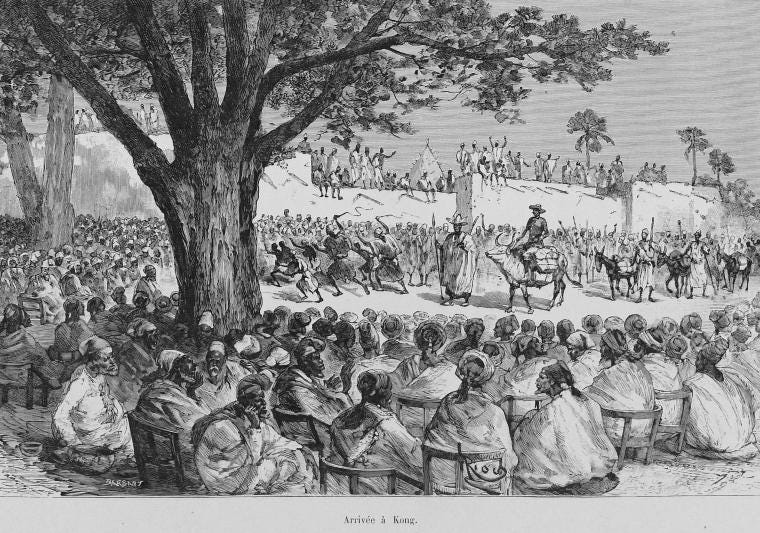

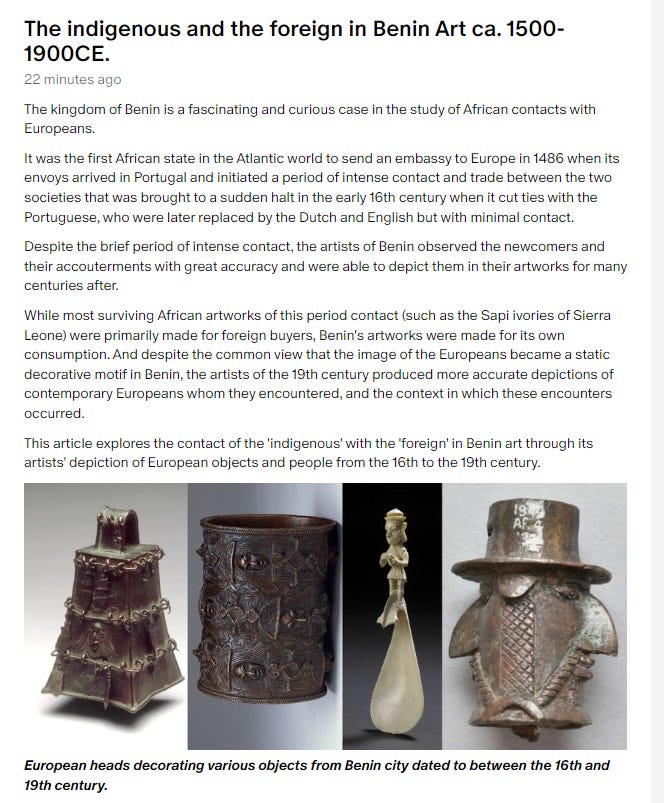

Most of the largest states in pre-colonial Africa were made up of culturally heterogeneous communities that were [products of historical processes](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-ethnicity-and-the?utm_source=publication-search) rather than ‘bounded tribes’ with fixed homelands.

The 19th-century kingdom of Adamawa represents one of the best case studies of a multi-ethnic polity in pre-colonial Africa, where centuries of interaction between different groups produced a veritable ethnic mosaic.

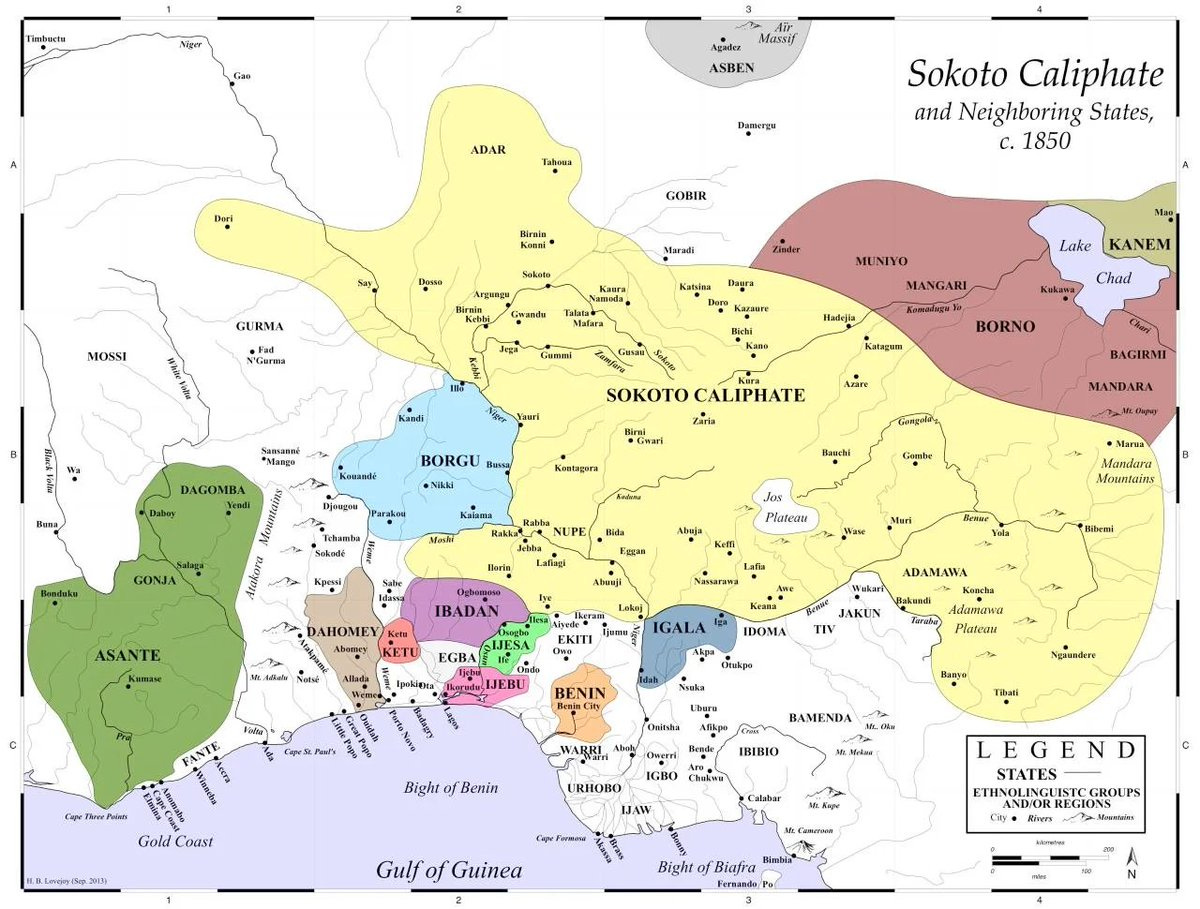

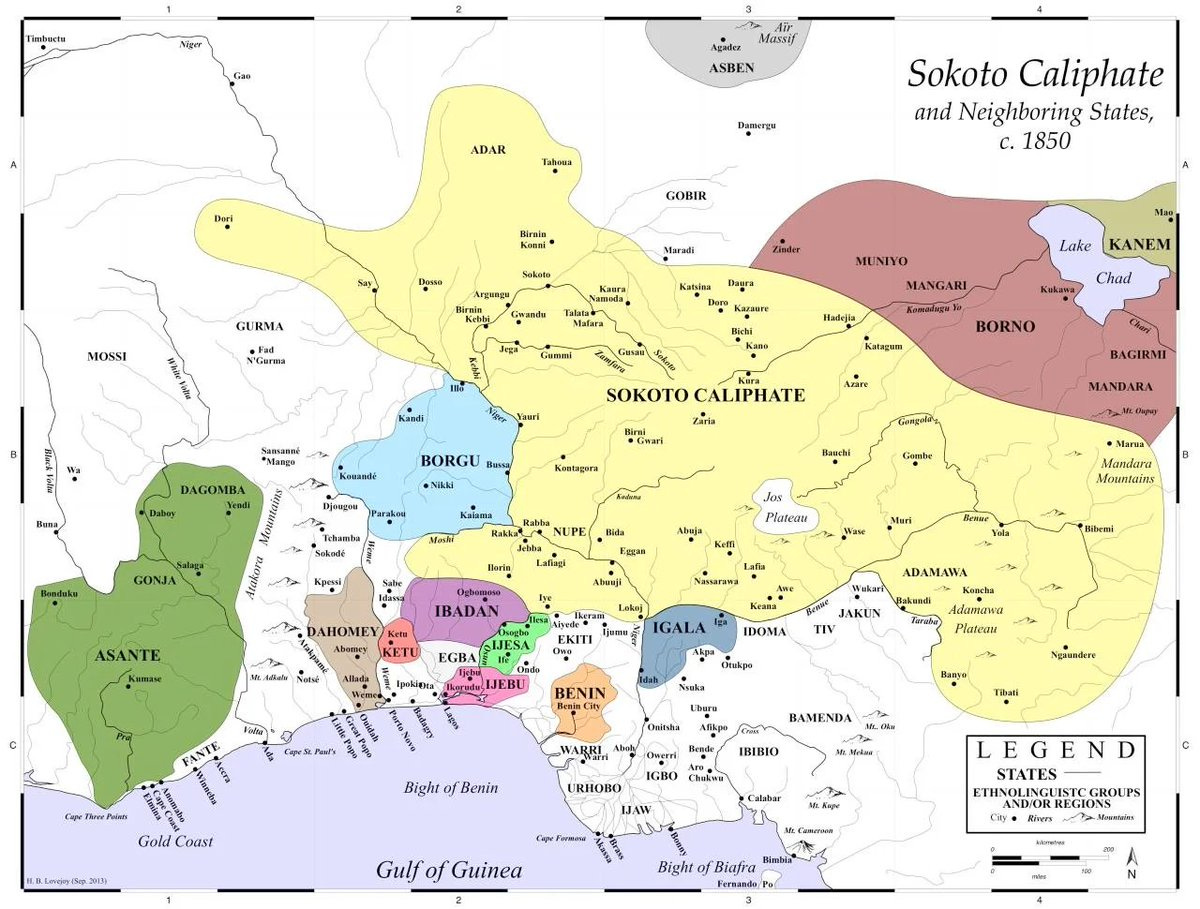

Established between the plains of the Benue River in eastern Nigeria and the highlands of Northern Cameroon, Adamawa was the largest state among the semi-autonomous provinces that made up the empire of Sokoto.

This article explores the social history of pre-colonial Adamawa through the interaction between the state and its multiple ethnic groups.

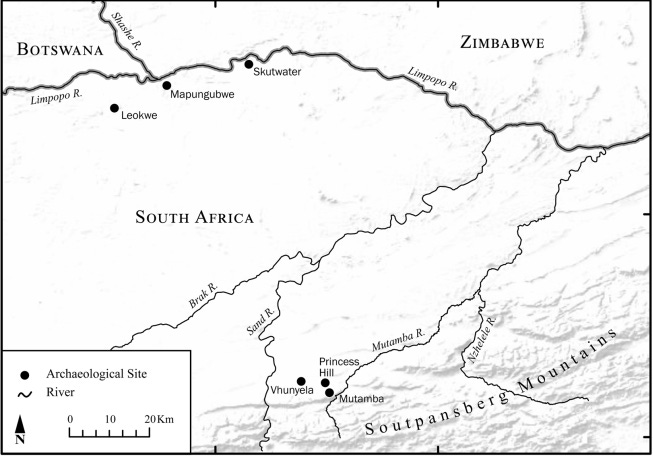

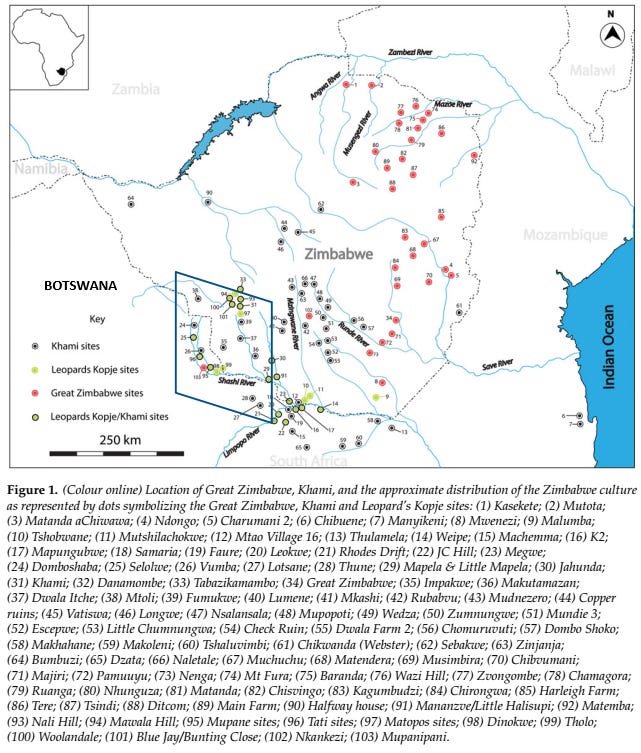

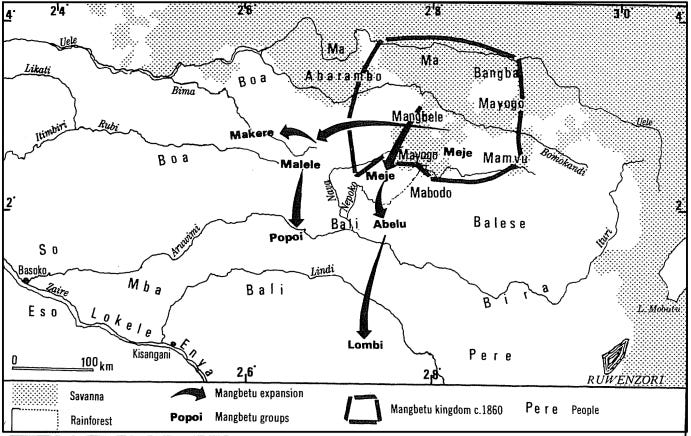

_**Map of 19th-century Adamawa and some of its main ethnic groups**_[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-1-167035963)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5MaD!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7fce441c-4c73-4a4f-b9ae-67696177d157_1338x657.png)

**Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

**Historical background: ethnogenesis and population movements in Fombina before the 19th century.**

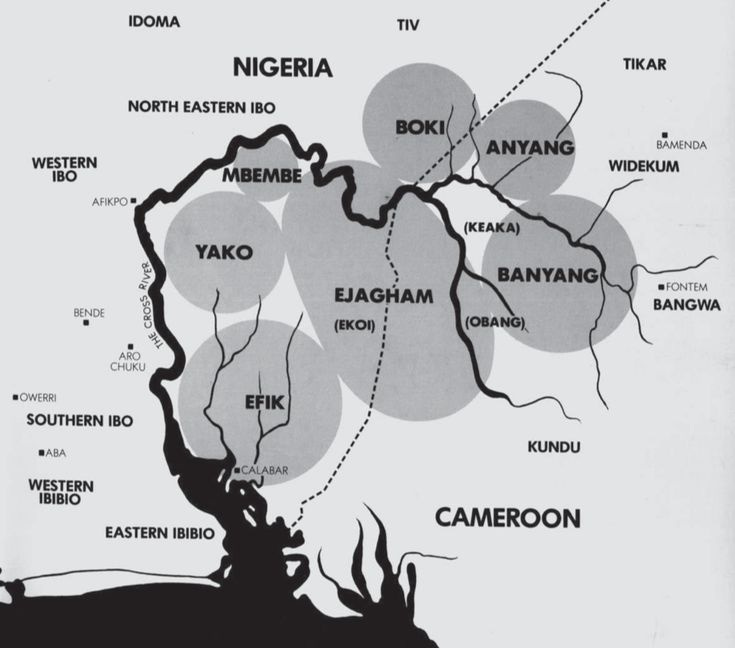

At the close of the 18th century, the region between Eastern Nigeria and Northern Cameroon was inhabited by multiple population groups living in small polities with varying scales of political organization. Some constituted themselves into chiefdoms that were territorially extensive, such as the Batta, Mbuom/Mbum, Tikar, Tchamba, and Kilba, while others were lineage-based societies such as the Vere/Pere, Marghi, and Mbula.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-2-167035963)

The Benue River Valley was mostly settled by the Batta/Bwatiye, who formed some of the most powerful polities before the 19th century as far north as the borders of Bornu and Mandara. According to the German explorer Heinrich Barth, who visited Adamawa in 1851, _**“it is their language**_[Batta]_**that the river has received the name Be-noë , or Be-nuwe, meaning ‘the Mother of Waters.’”**_[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-3-167035963)

The Adamawa plateau was mostly settled by the Mbum, who were related to the Jukun and Tchamba of the Benue valley and the Tikar of central Cameroon. They developed a well-structured social hierarchy with divine rulers (_Bellaka_) and exercised some hegemony over neighbouring groups.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-4-167035963)

According to the historian Eldridge Mohammadou, some of these groups were at one time members of the succession of Kwararafa confederations, which were potent enough to sack the Hausa cities of Kano, Katsina, and Zaria multiple times during the 16th and 17th centuries, and even besiege Ngazagarmu, the capital of the Bornu empire, before their forces were ultimately driven out of the region.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-5-167035963)

In the majority of the chieftaincies, a number of factors, such as kinship relations, language, religion, land, and the need for security, bound together the heterogeneous populations. Most chiefs were the political and religious heads of their communities; their authority was supported by religious sanctions. The polities had predominantly farming and herding economies, with marginal trade in cloth and ivory through the northern kingdoms of Bornu and Mandara.[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-6-167035963)

The political situation of the region changed dramatically at the turn of the 19th century following the arrival of Fulbe groups. The region settled by these Fulbe groups came to be known as Fombina, a Fulfulde term meaning ‘the southlands’.[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-7-167035963)

These groups, which had been present in the Hausalands and the empire of Bornu since the late Middle Ages, began their southward expansion in the 18th century. They mostly consisted of the Wollarbe/Wolarbe, Yillaga’en, Kiri’en, and Mbororo’en clans, who were mostly nomadic herders and the majority of whom remained non-Muslim until the early 19th century.[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-8-167035963)

Some of these groups also established state structures over pre-existing societies that would later be incorporated into the emirate of Adamawa. The Wollarbe, for example, were divided into several groups, each of which followed their leaders, known as the Arɗo. In 1870, the group under Arɗo Tayrou founded the town of Garoua in 1780 around settlements populated by the Fali, while around the same time, another group moved to the southeast to establish Boundang-Touroua around the settlements of the Bata.[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-9-167035963)

However, most of the Fulbe were subordinated to the authority of the numerous chieftains of the Fombina region, since acknowledgement of the autochthonous rulers was necessary to obtain grazing rights and security. Their position in the local social hierarchies varied, with some becoming full subjects in some societies, such as among the Higi and Marghi, while others were less welcome in societies such as the Batta of the Benue valley and the dependencies of the Mandara kingdom in northern Cameroon.[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-10-167035963)

**The Sokoto Empire and the founding of Adamawa.**

In the early 19th century, the political-religious movement of Uthman Dan Fodio, which preceded the establishment of the empire of Sokoto, and the expulsion of sections of the Fulbe from Bornu in 1807-1809 during the Sokoto-Bornu wars, resulted in an influx of Fulbe groups into Fombina. The latter then elected to send Modibo Adama, a scholar from the Yillaga lineage, to pledge their allegiance to the Sokoto Caliph/leader Uthman Fodio. In 1809, Modibo Adama returned with a standard from Uthman Fodio to establish what would become the largest emirate of the Sokoto Caliphate.[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-11-167035963)

Modibo Adama first established his capital at Gurin before moving it to Ribadou, Njoboli, and finally to Yola. As an appointed emir, he had defined duties and responsibilities over his officials, armed forces, tax collection, and obligations towards the Caliph, his political head and religious leader. His emirate, which was called Adamawa after its founder, eventually came to include over forty other units called _**lamidats**_ (sub-emirates), each with its _**Lamido**_ (chief) in his capital, and a group of officials similar to those in Yola.[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-12-167035963)

After initial resistance from established Fulbe groups, Modibo Adama managed to forge alliances with other forces, including among the non-Fulbe Batta and the Chamba. He raised a large force that engaged in a series of campaigns from 1811-1847 that managed to subsume the small polities of the region. The forces of Adamawa saw more success in the south against the chiefdoms of the Batta and the Tchamba in the Benue valley than in the north against the Kilba.[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-13-167035963)

In 1825, the Adamawa forces under Adama defeated the Mandara army and briefly captured the kingdom's capital, Dolo, but were less successful in their second battle in 1834. This demonstration of strength compelled more local rulers to submit to Adama's authority, which, together with further conquests against the Mbum in the south and east, created more sub-emirates and expanded the kingdom.[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-14-167035963)

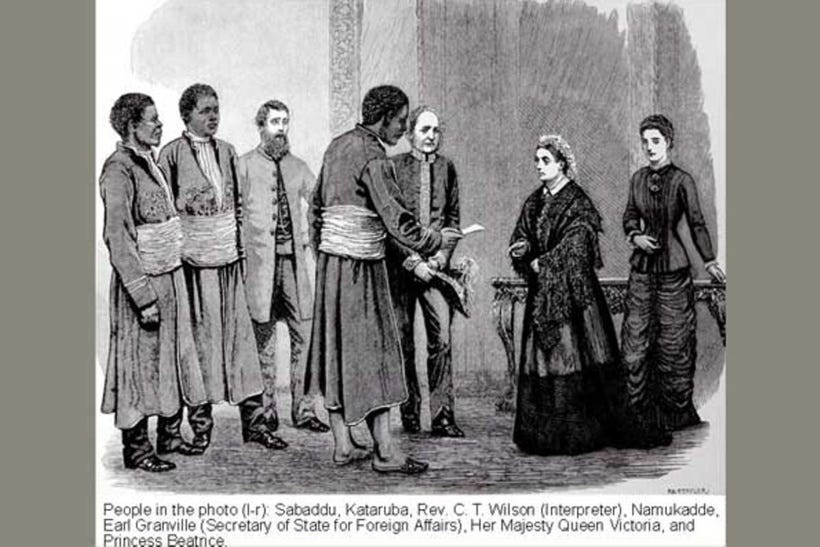

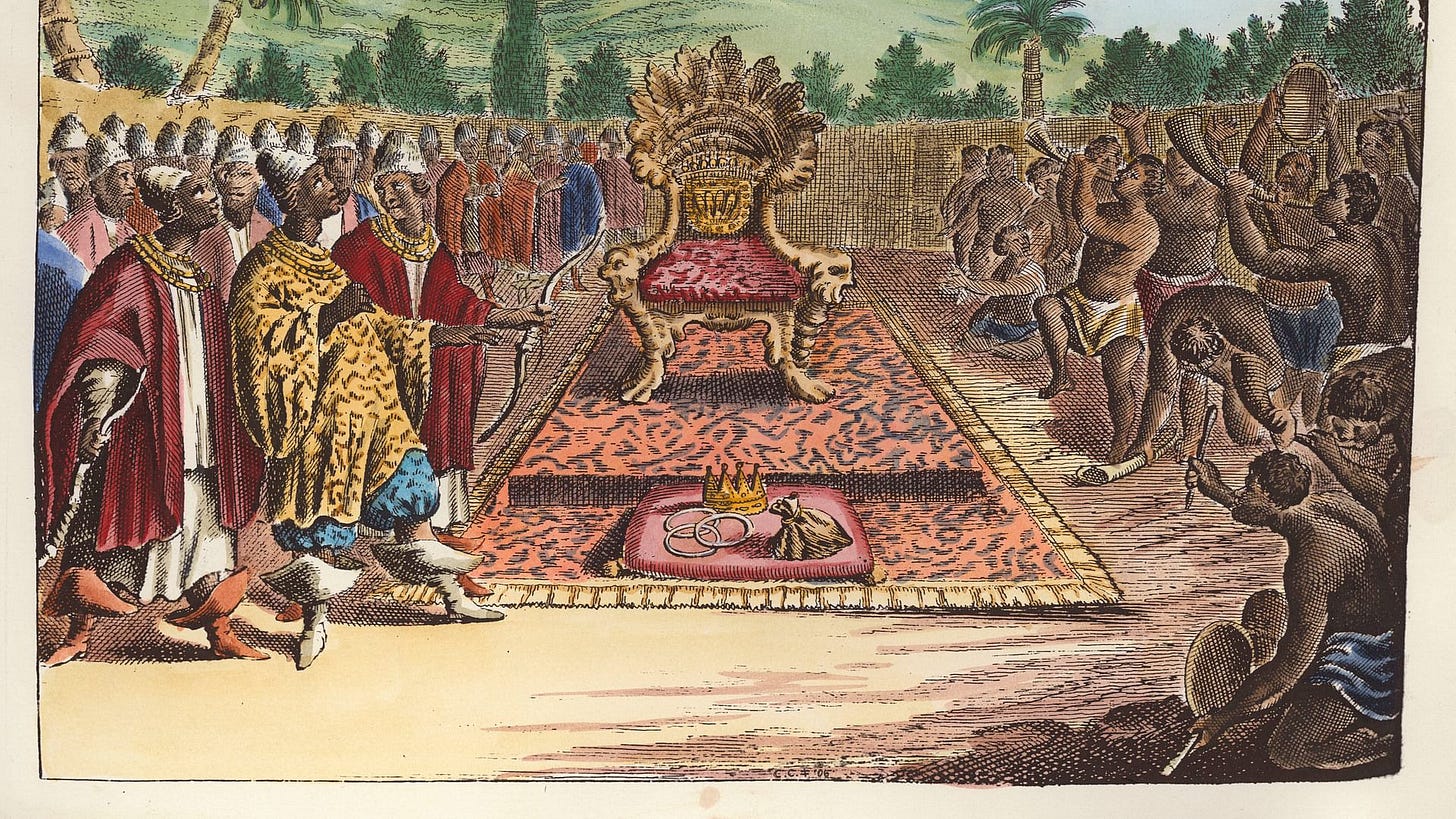

In Cameroon, several Wollarɓe leaders received the permission of Modibo Adama to establish lamidats in the regions of Tibati (1829), Ngaoundéré (1830), and Banyo (1862). The majority of the subject population was made up of the Vouté/Wute, Mbum, and the Péré. Immigrant Kanuri scholars also made up part of the founding population of Ngaoundéré, besides the Fulbe elites. It was the Banyo cavalry that assisted [the Bamum King Njoya](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-invention-of-writing-in-an-african) in crushing a local rebellion.[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-15-167035963)

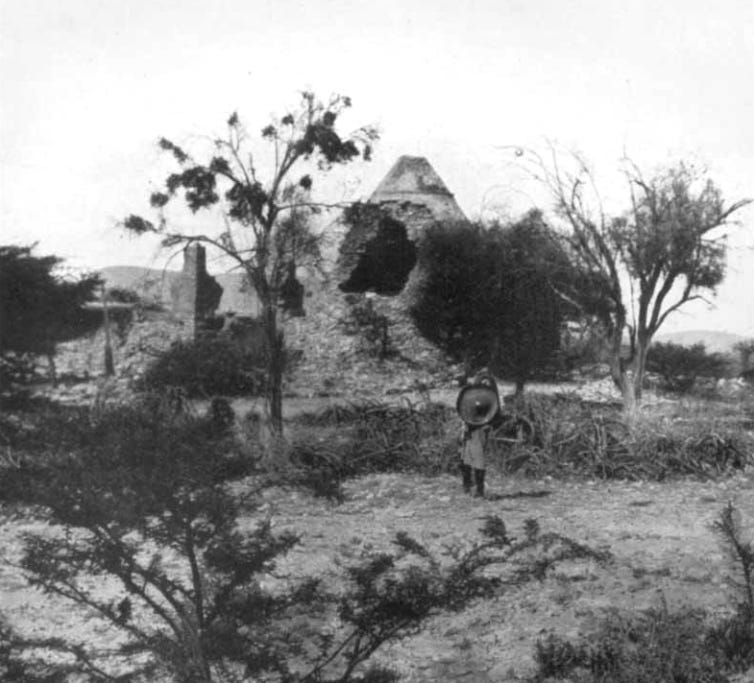

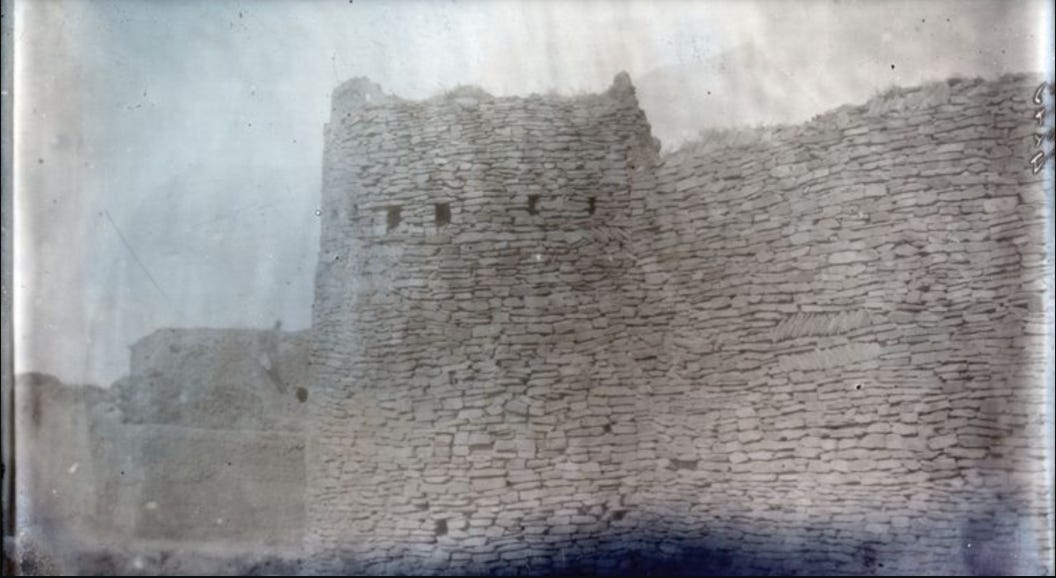

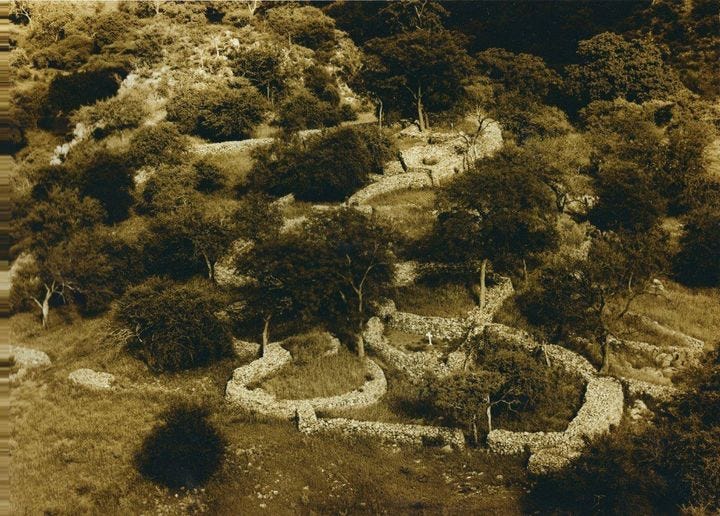

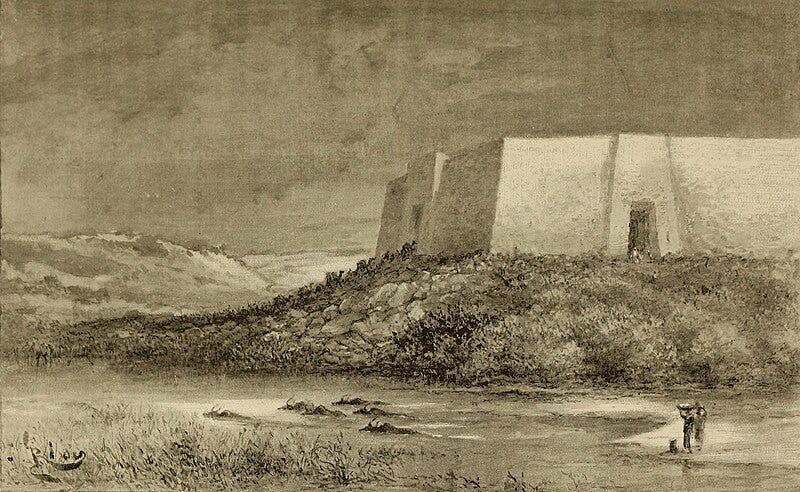

A group of lamidats was also established in the northernmost parts of Cameroon by another clan of Fulɓe, known as the Yillaga’en, who founded the lamidats of Bibèmi and Rey-Bouba, among others. The lamidat of Rey in particular is known for its strength and wealth, and for its opposition to incorporation into the emirate, resulting in two wars with the forces of Yola in 1836 and 1837.[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-16-167035963)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8fRE!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F07438da9-57fb-4d24-87c6-783ee96905a4_736x545.png)

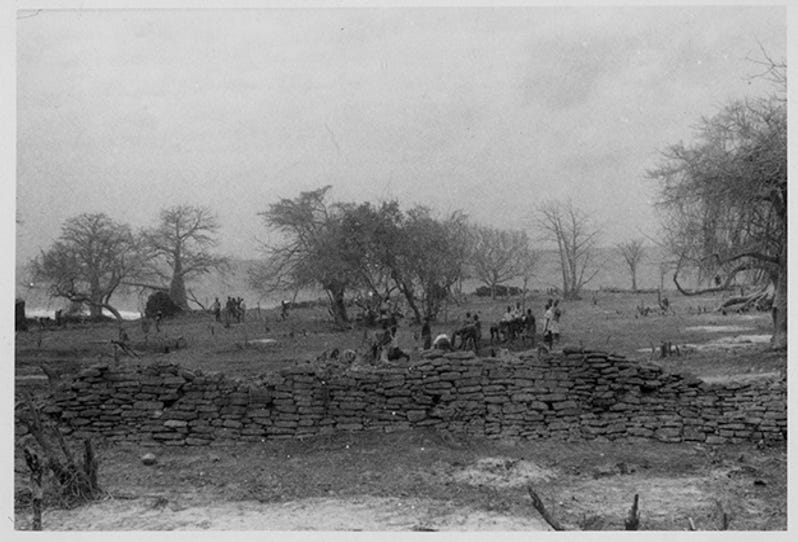

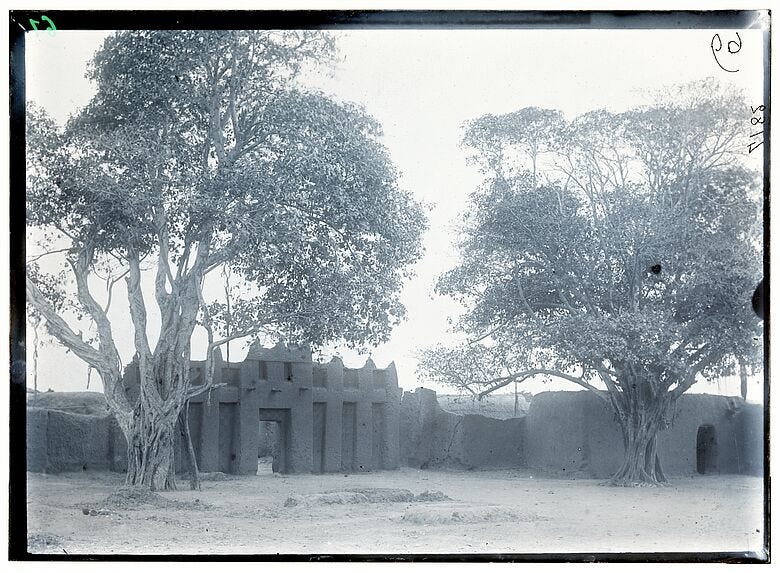

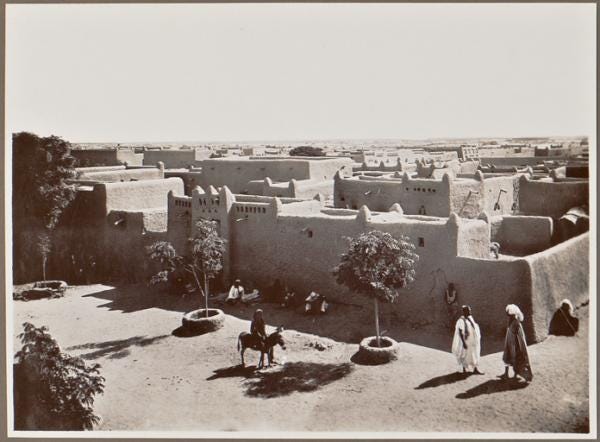

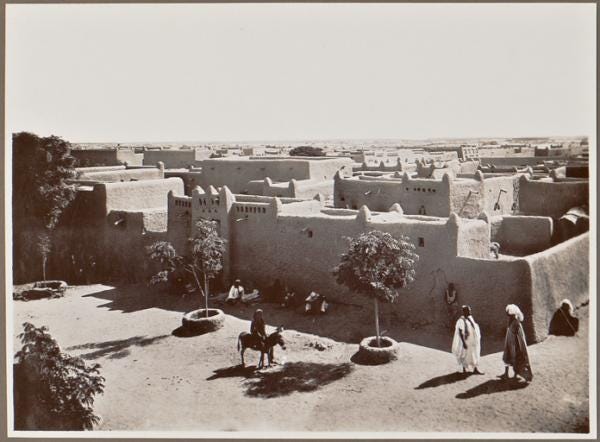

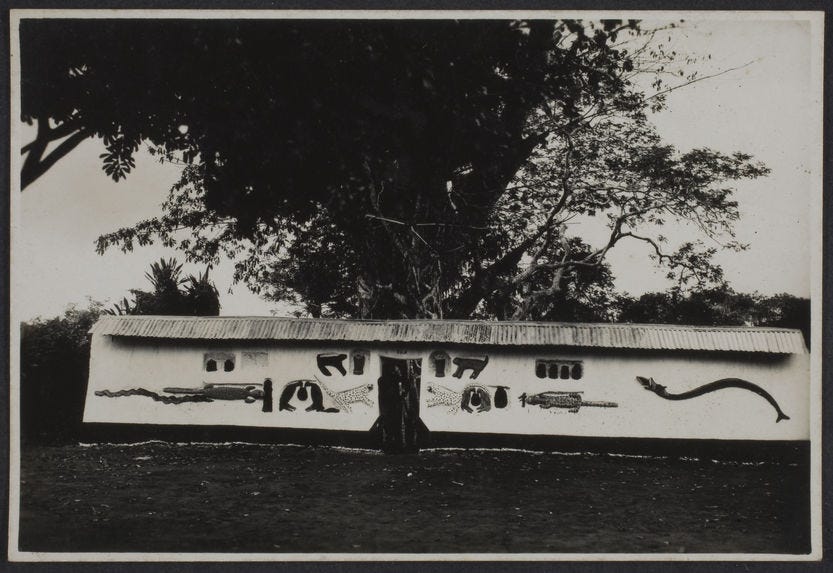

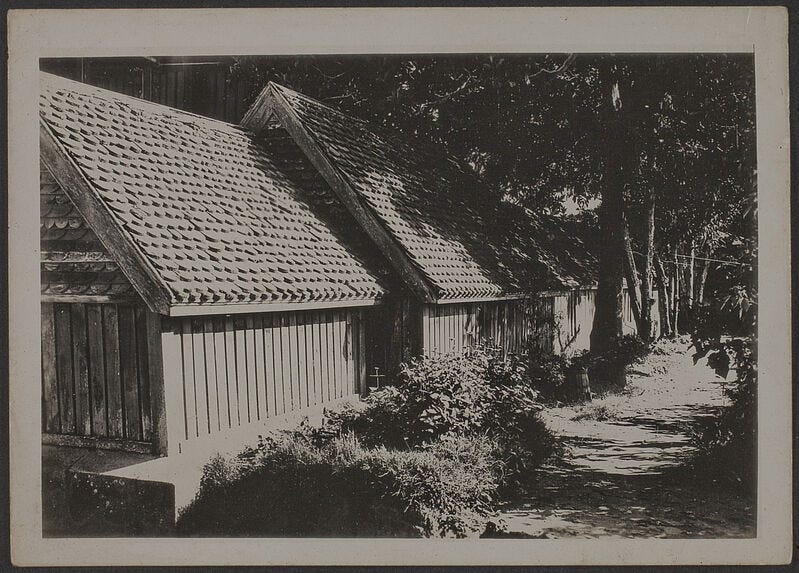

_**Entrance to the Palace at Rey, Cameroon**_. ca 1930-1940. Quai Branly.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xrtP!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb605eaa3-8b17-48b9-b35d-cae70949feb8_576x573.png)

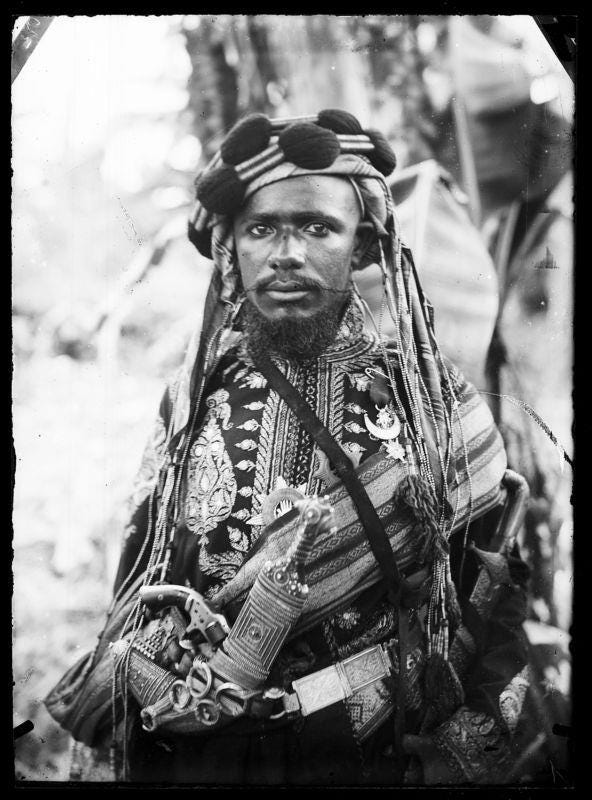

_**Horsemen of Rey, Cameroon. ca. 1932**_. Quai Branly

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xx0L!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9c7ca74e-da1e-4aa9-a325-5fbf670b6455_889x602.png)

_**‘Knights of the Lamido of Bibémi’**_ Cameroon, ca. 1933. Quai Branly.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Rrxp!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6a559b8d-37e8-4440-8a46-c350425654a7_827x593.png)

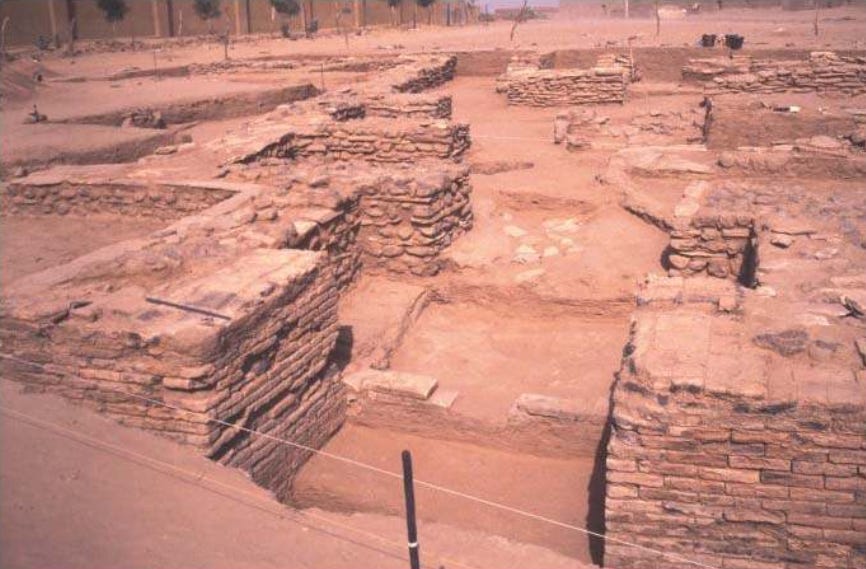

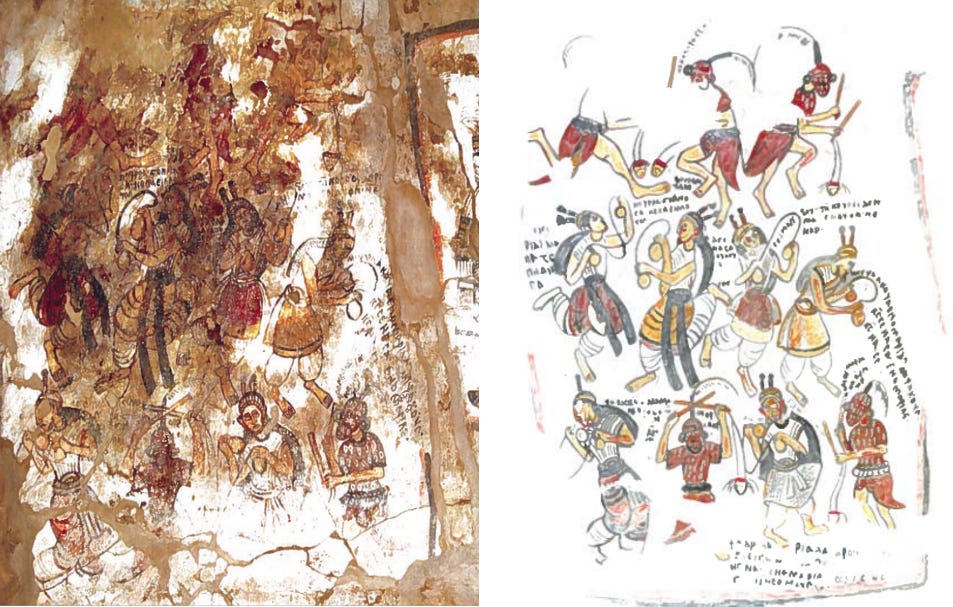

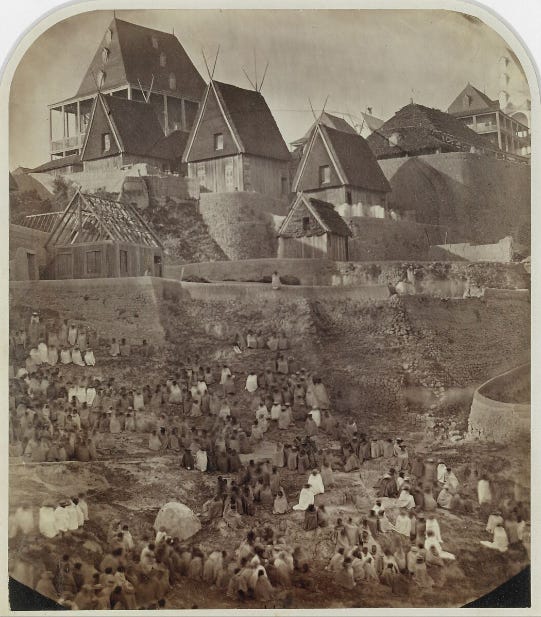

_**an early 20th century illustration by a Bamum artist depicting the civil war of the late 19th century at Fumban and the alliance between Adamawa and Bamum to secure Njoya’s throne.**_ (Musée d'ethnographie de Genève Inv. ETHAF 033558)

**State and society in 19th-century Adamawa**

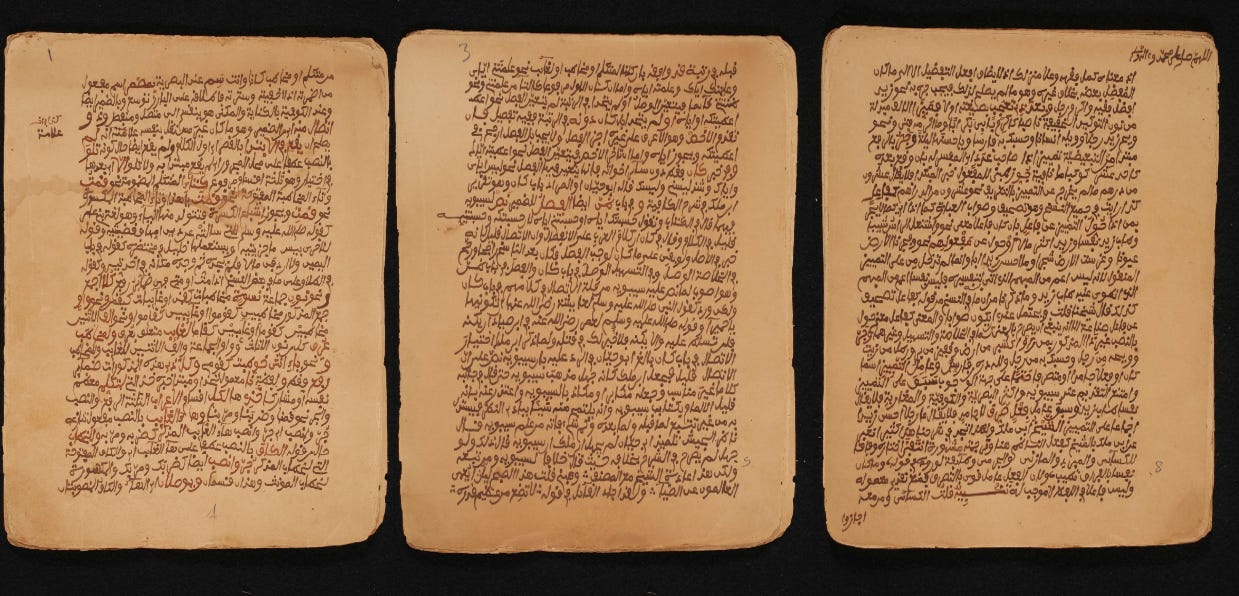

By 1840, the dozens of sub-emirates had been established across the region. Modibbo Adama, as the man to whom command was delegated, played the role of the Shehu in the distribution of flags to his subordinates. While all the lamidats were constituent sub-states within the emirate of Adamawa, they were allowed a significant degree of local autonomy. Each ruler could declare war, arrange for peace, and enter into alliances with others without reference to Yola.[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-17-167035963)

Relations between Sokoto, Adamawa, and its sub-emirates began to take shape during the reign of Adama’s successor, Muhammad Lawal (r. 1847-1872). Contact with outside regions, which was hitherto limited, was followed by increased commerce with Bornu and Hausaland. Prospects for trade, settlement, and grazing attracted immigrant Fulbe, Hausa, and Kanuri traders into the emirate, further contributing to the region's dynamic social landscape.[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-18-167035963)

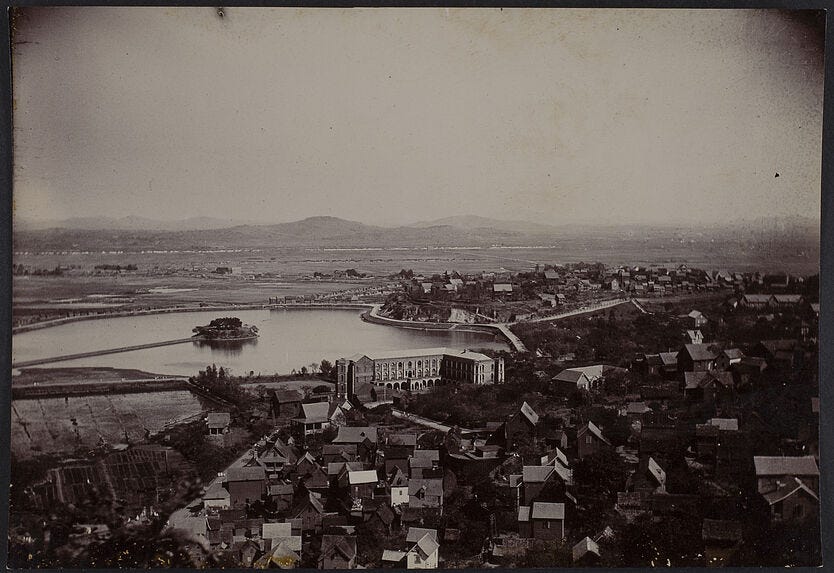

The borders of the Emirate were extended very considerably during the reign of Lawal, from the Lake Chad basin in the north, to Bouar in what is now the Central African Republic in the east, and as far west as the Hawal river. The emirate government of Fombina became more elaborate, and multiple offices were created in Yola to centralise its administration, with similar structures appearing in outlying sub-emirates.[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-19-167035963)

In many of the outlying sub-emirates, local allies acknowledged Adamawa’s suzerainity and thus retained their authority, such as in Tibati, Rey, Banyo, Marua, and Ngaoundéré. The local administration thus reflected the sub-emirate’s ethnic diversity, with two groups of councillors: one for the Fulbe and another for the autochthonous groups.[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-20-167035963)

In the city of Ngaoundéré, for example, the governing council (_faada_) was comprised of three bodies for each major community: the _Kambari faada_, for Hausa and Kanuri notables, the _Fulani faada_ for Fulbe, and the _Matchoube faada_ for the Mbum chiefs. The Mbum chiefs had established matrimonial alliances with the Fulbe and were allowed significant autonomy, especially in regions beyond the capital. Chieftains from other groups, such as the Gbaya and the Dìì, were also given command of the periphery provinces and armies, or appointed as officials to act as buffers between rivaling Fulbe aristocrats.[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-21-167035963)

Writing on the composition of the Yola government in the mid-19th century, the German explorer Heinrich Barth indicated that there was a Qadi, Modibbo Hassan, a ‘secretary of state’, Modibbo Abdullahi, and a commander of troops, Ardo Ghamawa. Other officials included the Kaigama, Sarkin Gobir, Magaji Adar, and Mai Konama. Despite the expansion of central authority, some of the more powerful local rulers retained their authority, especially the chiefs of Banyo, Koncha, Tibati, and Rey, but continued to pay tribute to the emir at Yola.[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-22-167035963)

Additionally, many of the powerful autochthons that had accepted the suzerainty of Adamawa and were allowed to retain internal autonomy resisted Lawal’s attempts at reducing them to vassalage. The Batta chieftains, including some of those living near the capital itself, took advantage of the mountainous terrain to repel the cavalry of the Fuble and even assert ownership of the surrounding plains. These and other rebellions compelled Lawal to establish _**ribat**_ s (fortified settlements) with garrisoned soldiers to protect the conquered territories.[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-23-167035963)

As Heinrich Barth observed while in Adamawa: _**“The Fúlbe certainly are always making steps towards subjugating the country, but they have still a great deal to do before they can regard themselves as the undisturbed possessors of the soil.”**_ adding that _**“the territory is as yet far from being entirely subjected to the Mohammedan conquerors, who in general are only in possesion of detached settlements, while the intermediate country, particulary the more mountainous tracts, are still in the hands of the pagans.”**_[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-24-167035963)

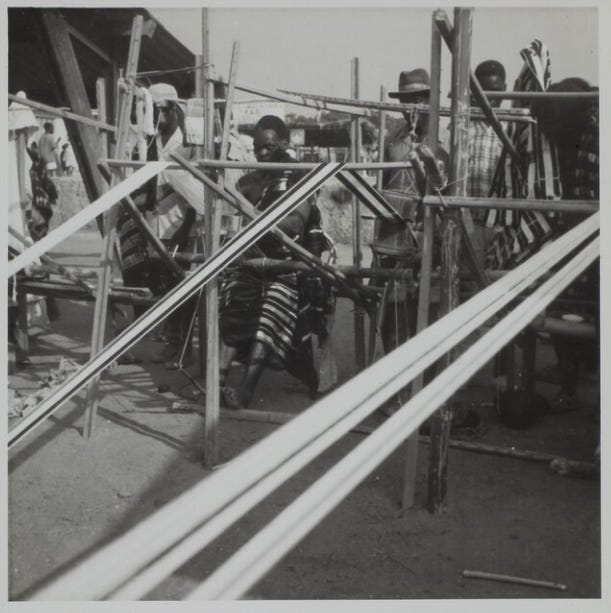

This constant tension between the rulers at Yola, the semi-independent sub-emirates, the autochthonous chieftains, and the independent kingdoms at nearly all frontiers of Adamawa, meant that war was not uncommon in the emirate. Such conflicts, which were often driven by political concerns, ended with defeated groups being reduced to slavery or payment of tribute. [Like in Sokoto](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/an-empire-of-cloth-the-textile-industry#footnote-anchor-9-150446951), the slaves were employed in various roles, from powerful officials and soldiers to simple craftsmen and cultivators on estates (which Barth called ‘_rumde_’), where they worked along with other client groups and dependents.[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-25-167035963)

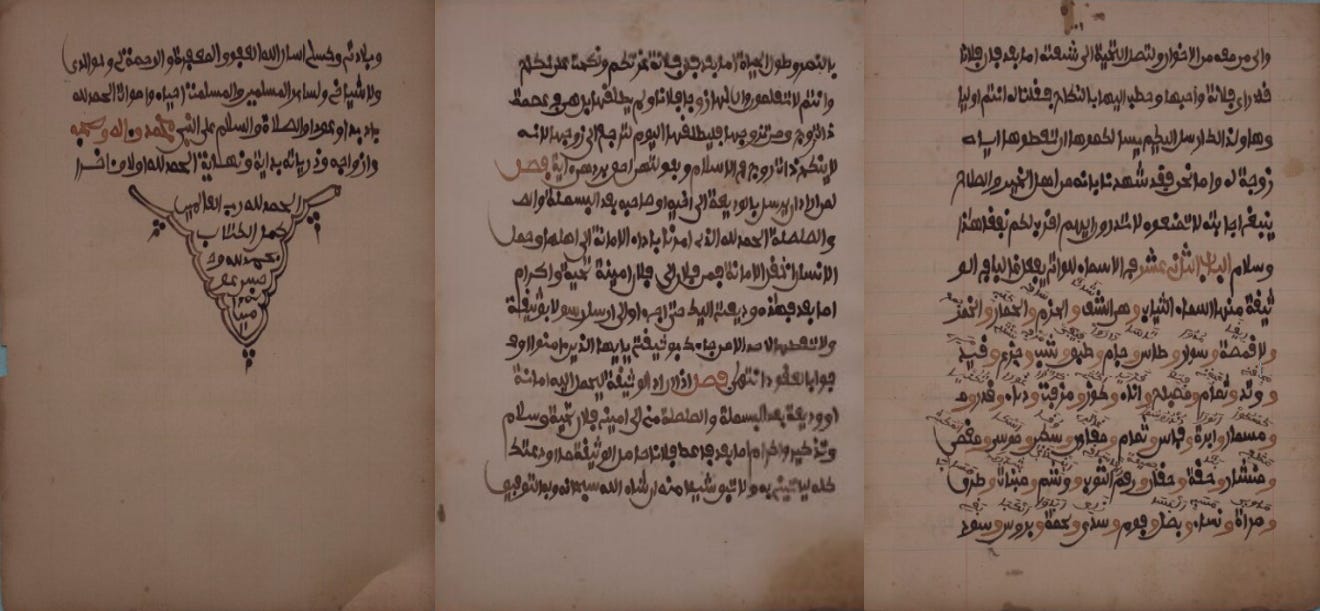

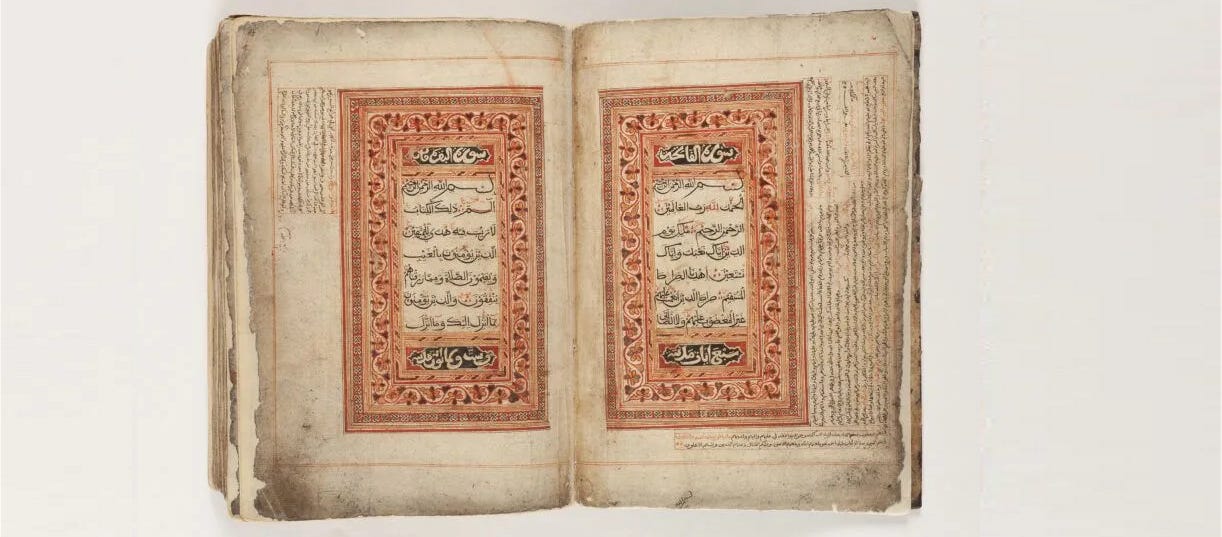

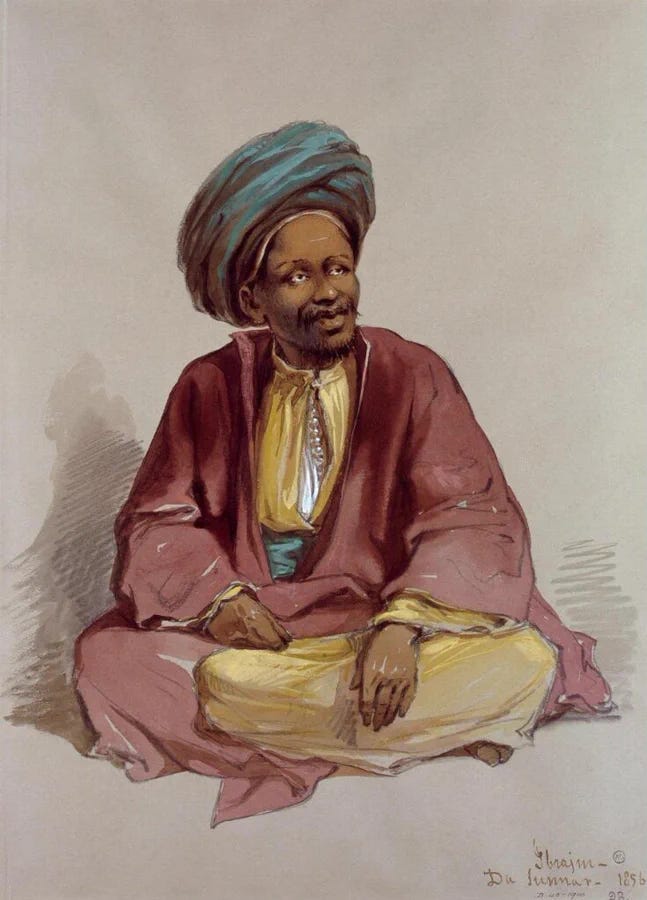

The influx of Hausa, Fulbe, and Kanuri merchant-scholars gradually altered the cultural practices of the societies in Fombina. The Hausa in particular earned the reputation of being the most travelled and versatile merchants in Adamawa. They are first mentioned in Barth's description of Adamawa but likely arrived in the region before the 19th century for various reasons. Some were mercenaries, others were malams (teachers), and others were traders.[26](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-26-167035963)

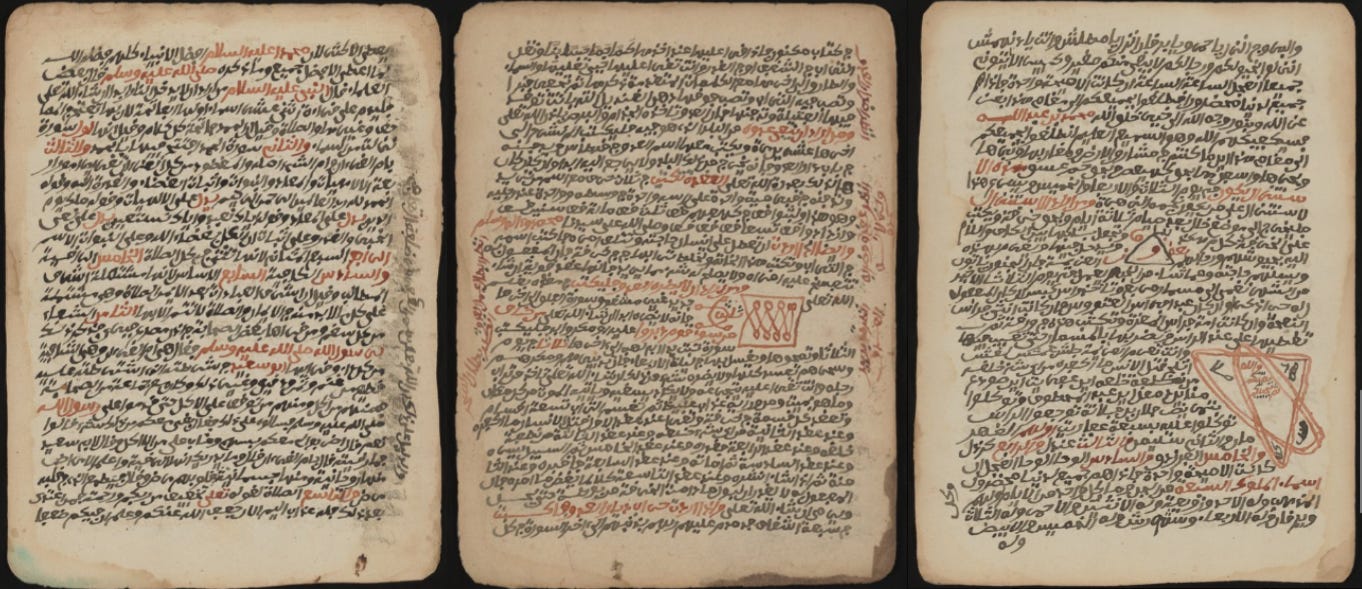

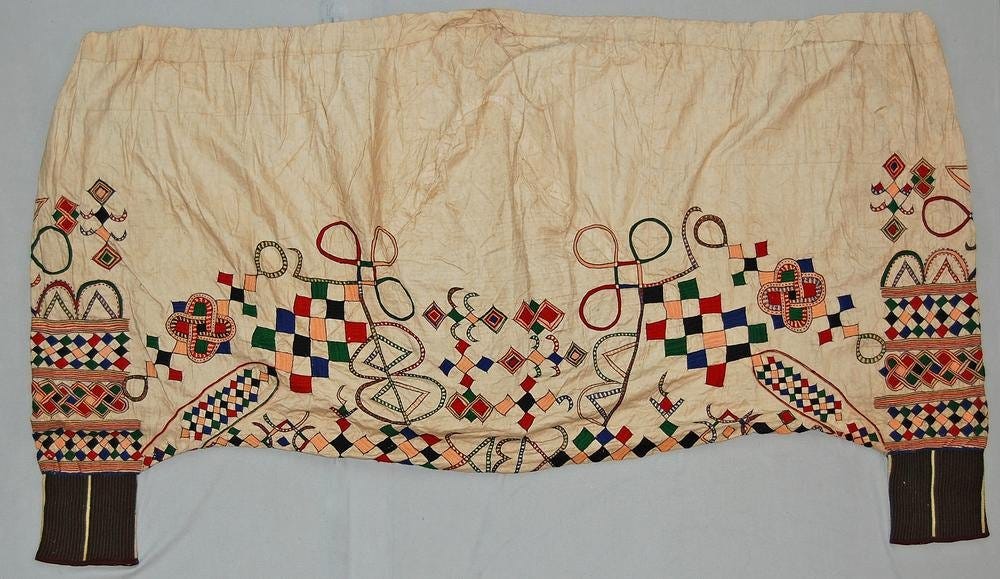

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kNXA!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd9ee6490-f0d9-41aa-b28d-177d44cd1ac2_942x459.png)

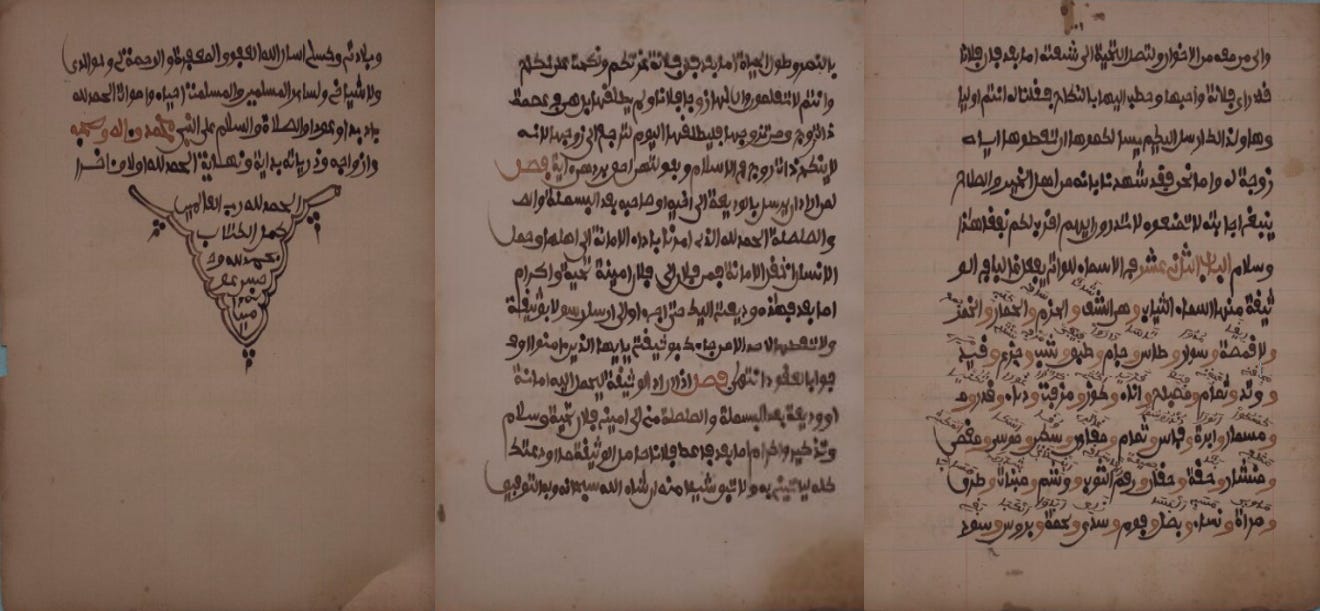

_**Writing board and dyed-cotton robe**_, 19th century, Adamawa, Cameroon. Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

The rulers at Yola encouraged scholars to migrate from the western provinces of Sokoto. Some served in the emirate's administration, while others founded towns that were populated with their students, eg, the town of Dinawo, which was founded in 1861 by the Tijanniya scholar and Mahdi claimant Modibbo Raji. The founding of mosques and schools meant that Islam and some of the cultural markers of Hausaland were adopted among some of the autochthons and even neighbouring kingdoms like Bamum, but most of the subject population retained their traditional belief systems.[27](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-27-167035963)

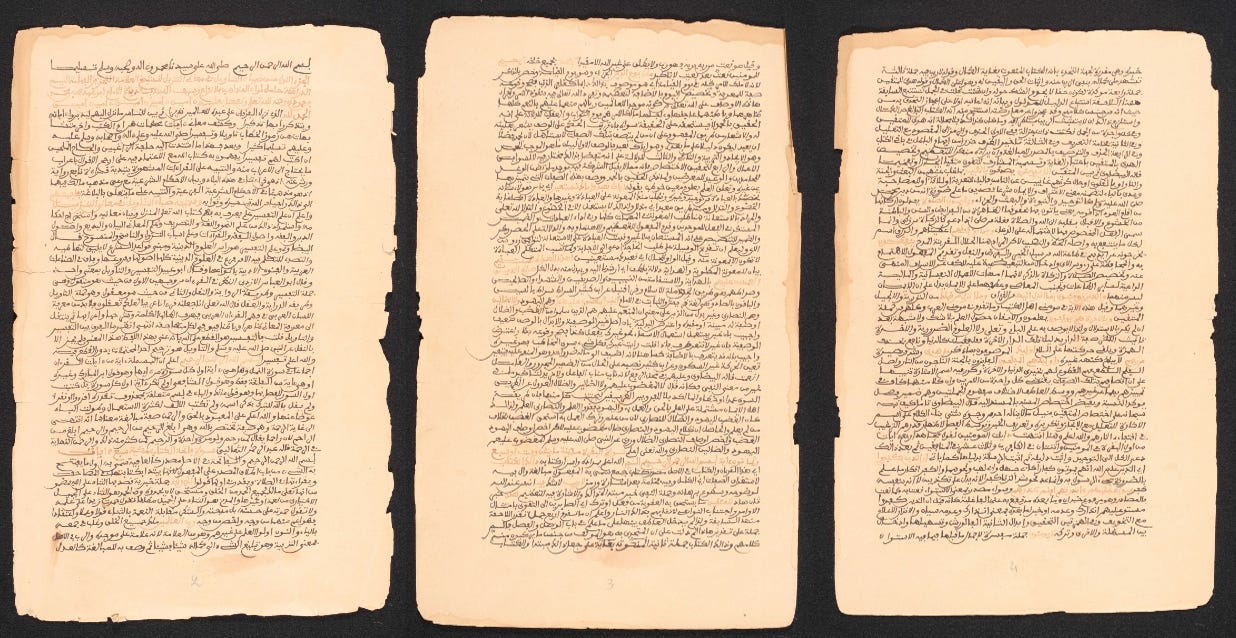

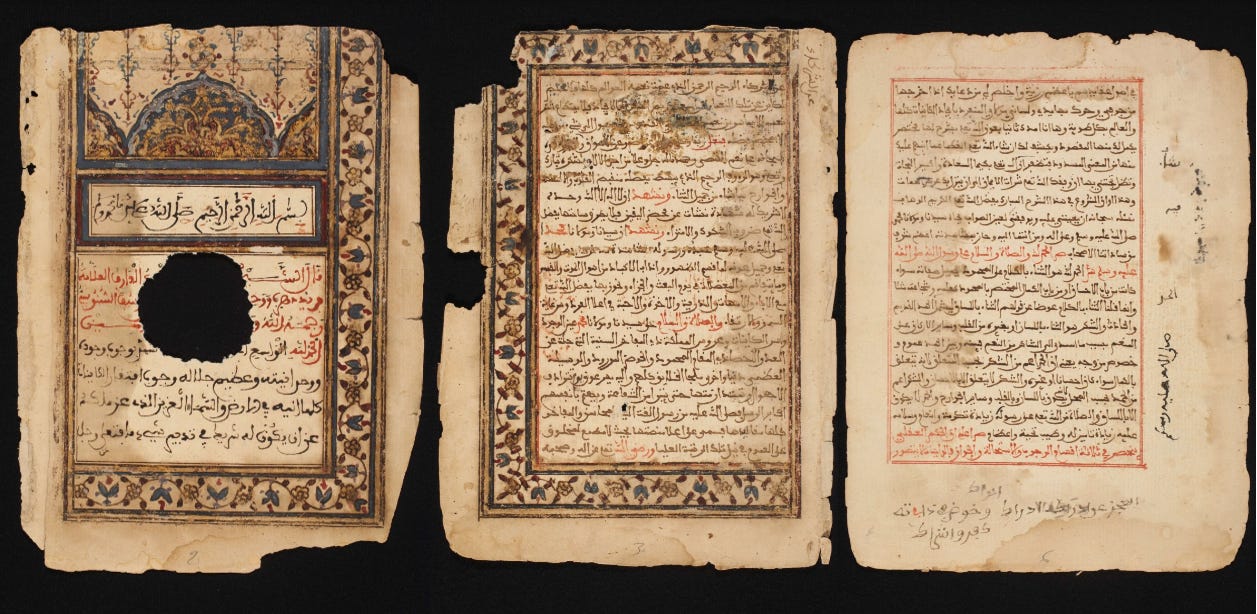

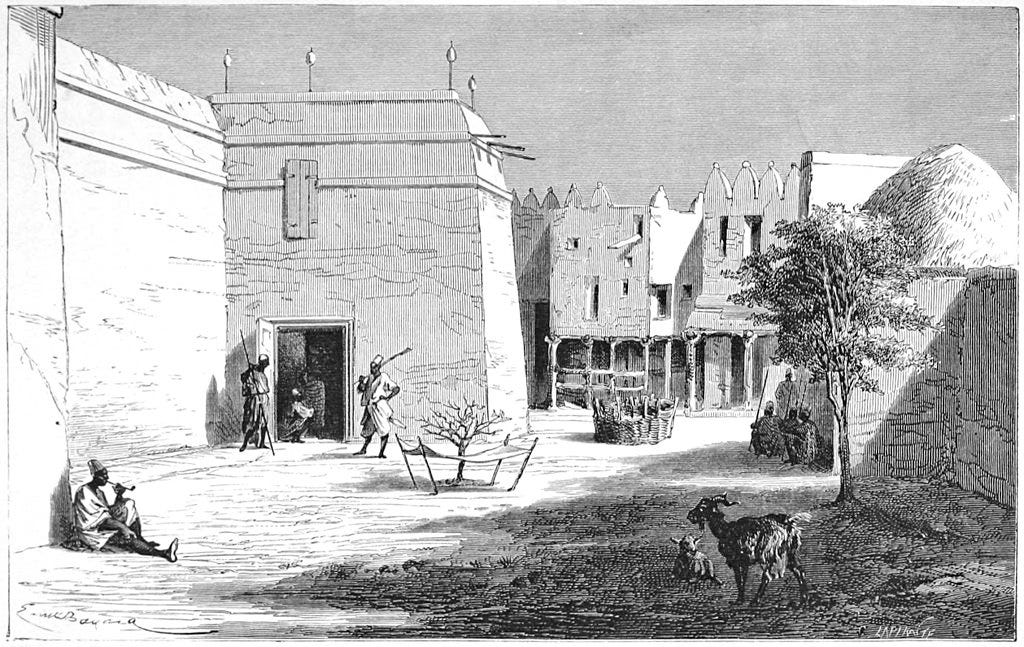

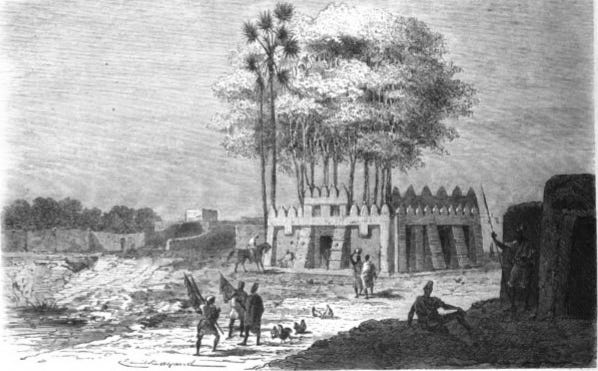

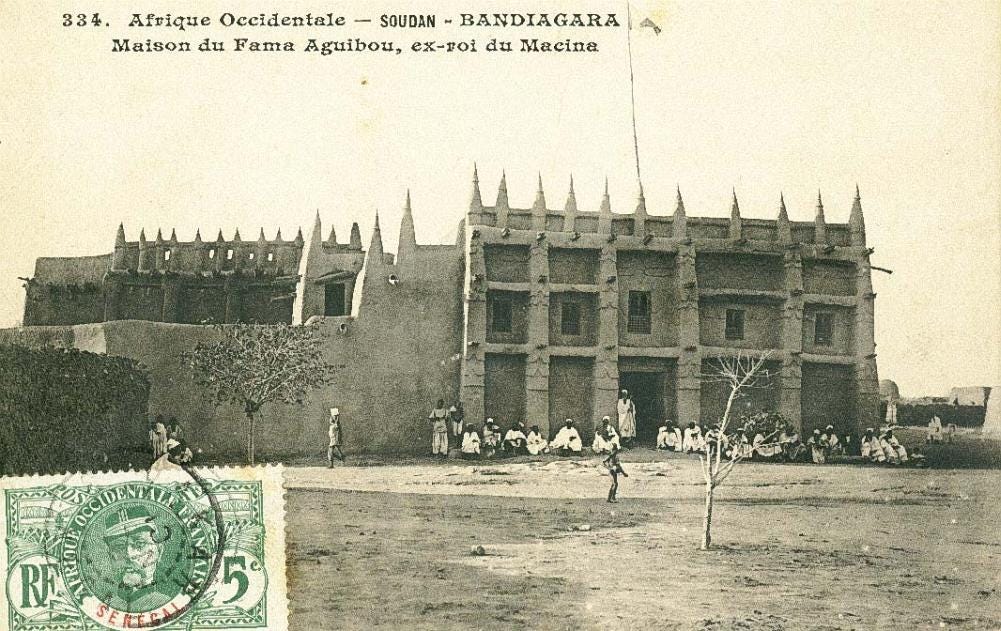

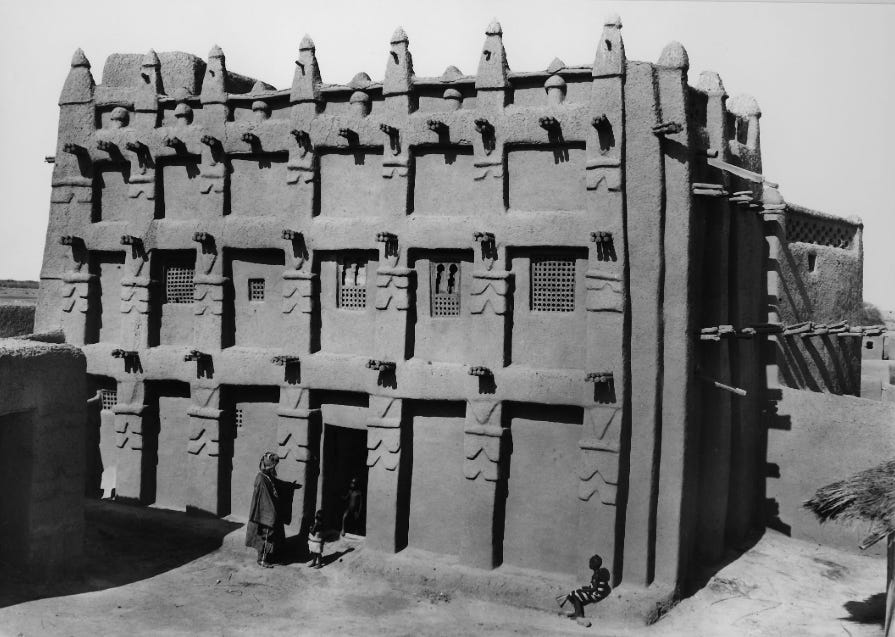

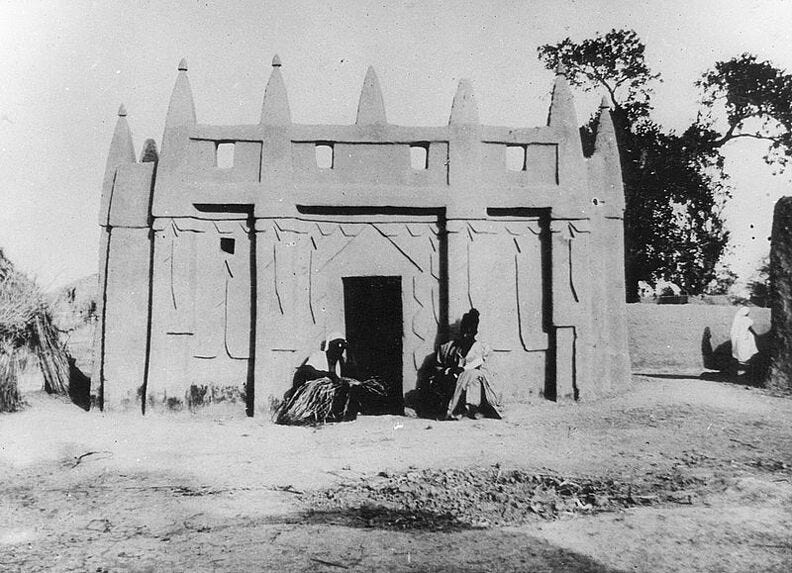

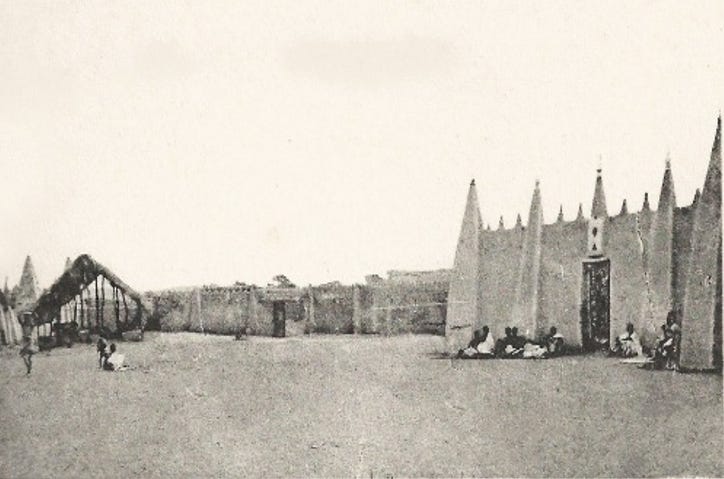

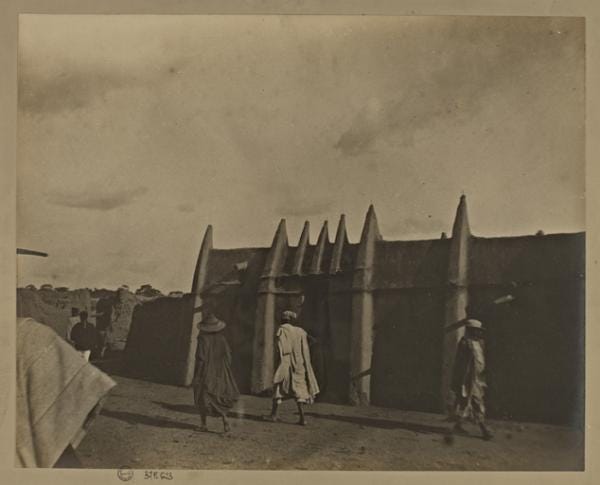

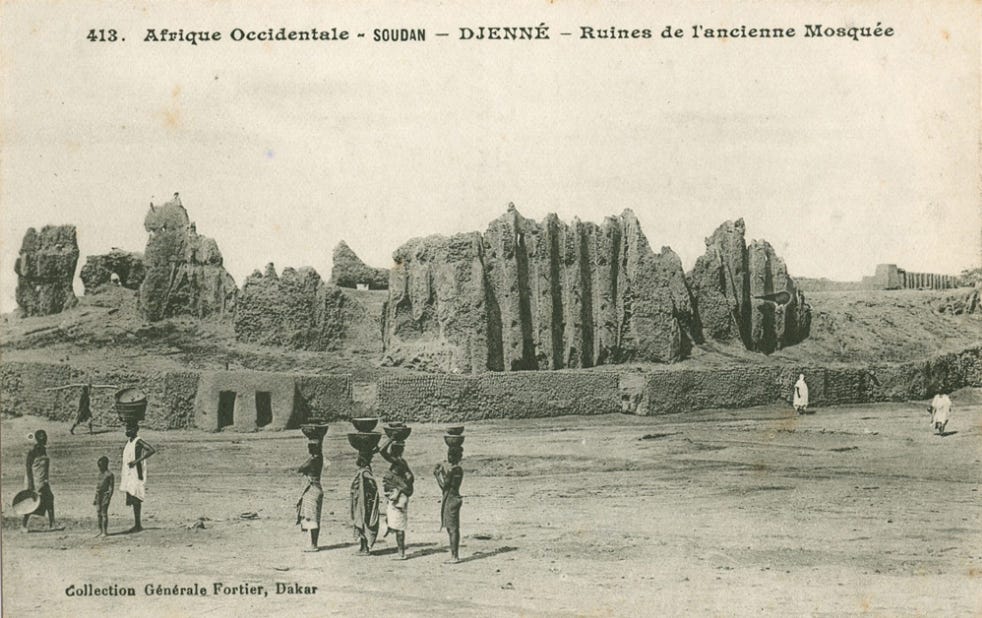

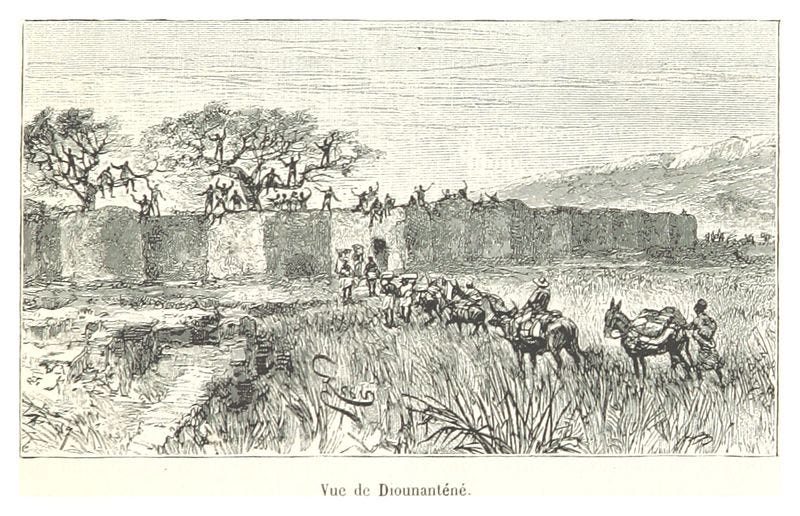

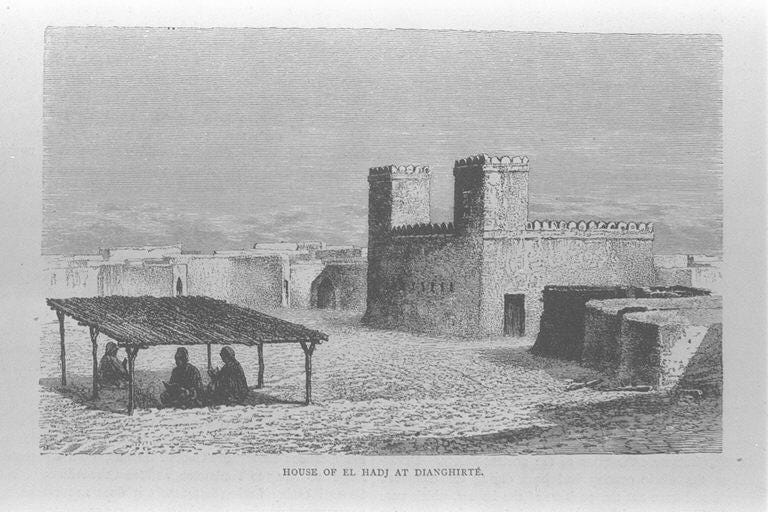

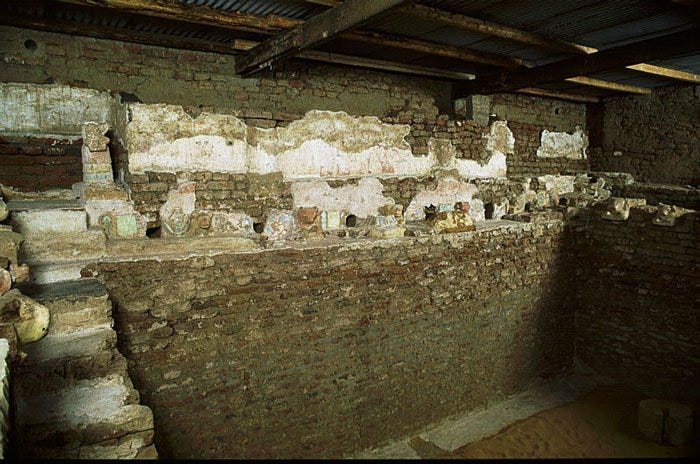

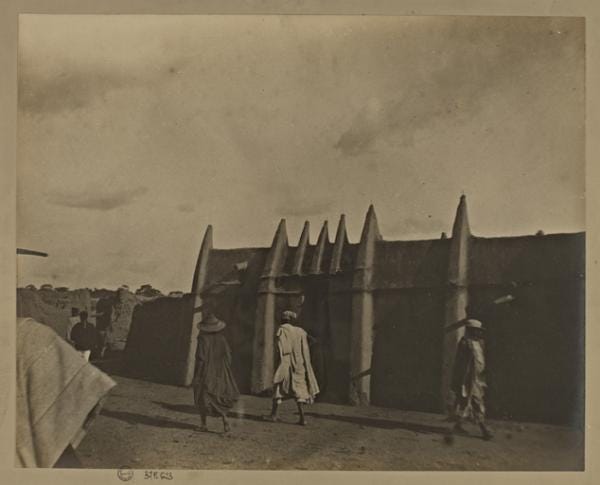

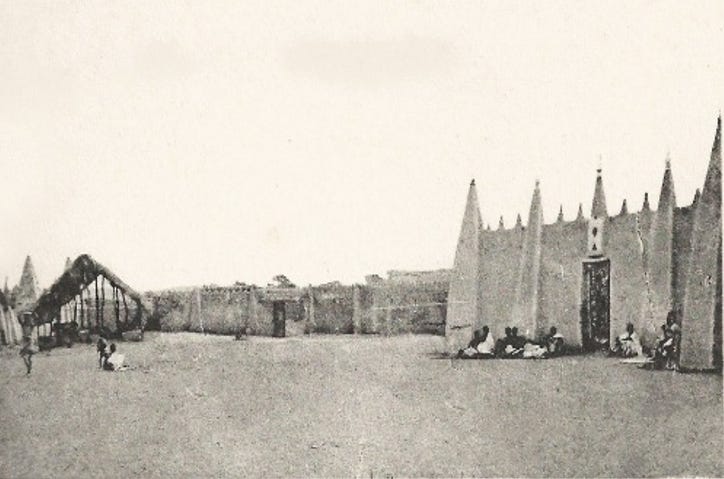

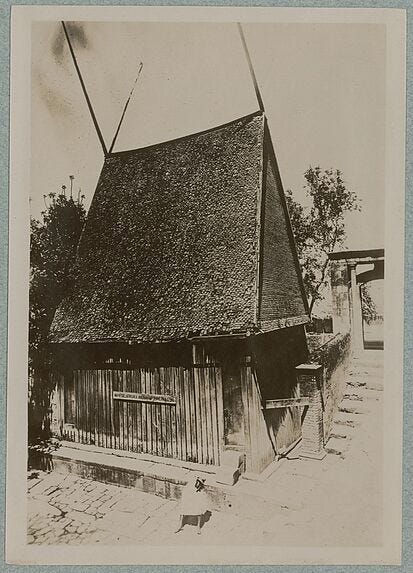

The diversity of the social makeup of Adamawa was invariably reflected in its hybridised architectural style, which displays multiple influences from different groups, and is the most enduring legacy of the kingdom.

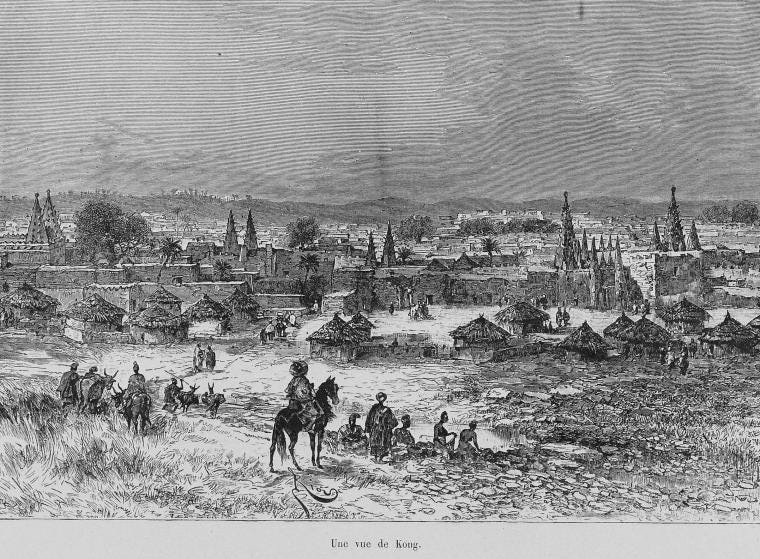

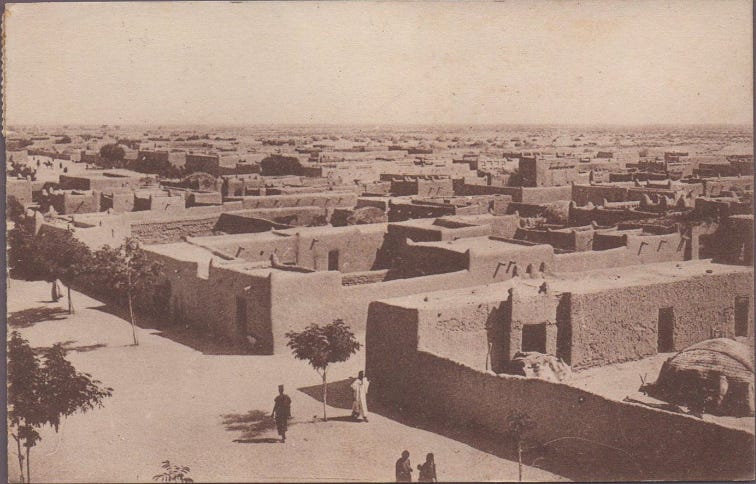

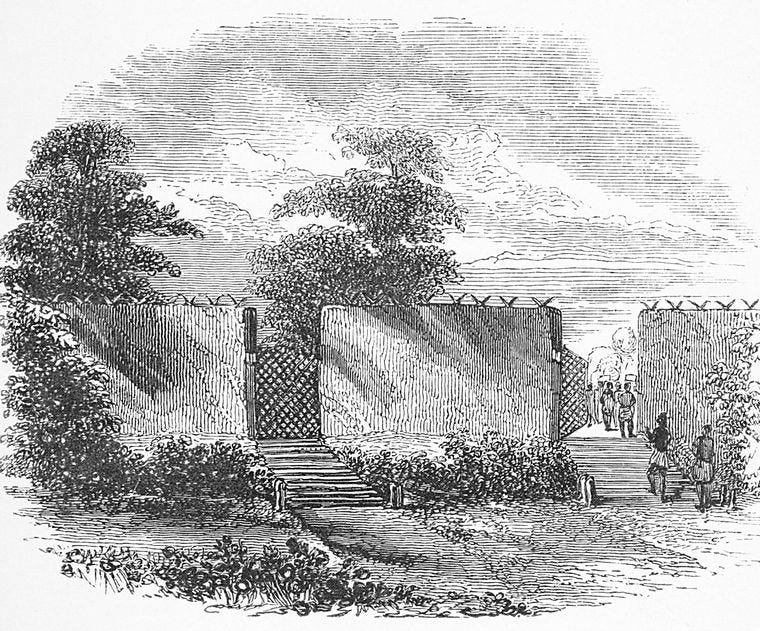

The presence of walled towns, especially in northern Cameroon, is mentioned by Heinrich Barth, who notes that Rey-Bouba, alongside Tibati, was _**“the only walled town which the Fulbe found in the country; and it took them three months of continual fighting to get possession of it.”**_[28](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-28-167035963) Walled towns were present in the southern end of the Lake Chad basin since the Neolithic period, and became a feature of urban architecture across the region from [the Kotoko towns in northern Cameroon](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-political-history-of-the-kotoko) to the [Hausa city states in northern Nigeria](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-history-of-the-hausa-city-states?utm_source=publication-search).

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!clic!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F620e2911-8eb8-4b54-83b0-068b284d6090_1048x442.png)

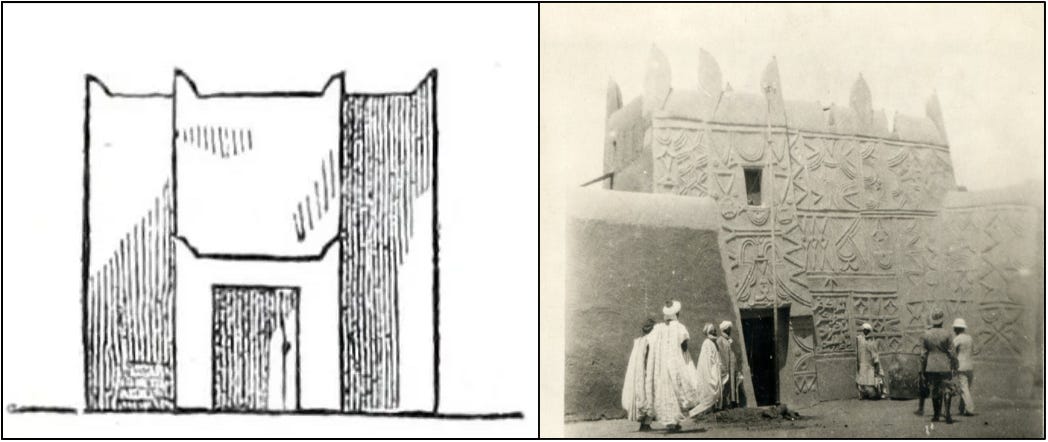

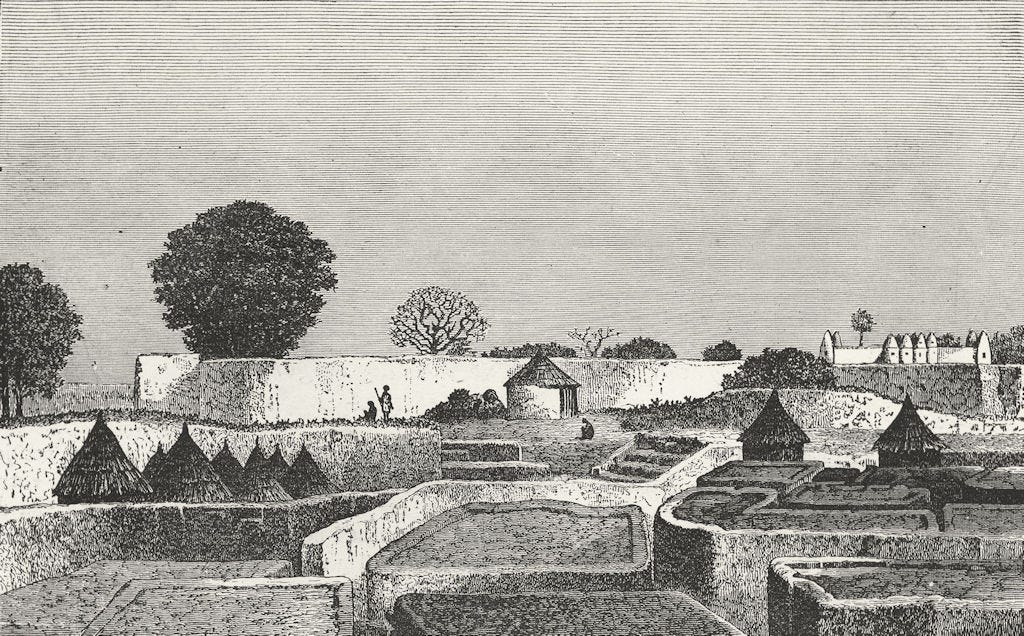

(left) _**Illustration of Lamido Muhammad Lawal’s palace at Yola by Heinrich Barth**_. (right) _**decorated facade of one of the entrances to the palace of Kano, Nigeria**_.

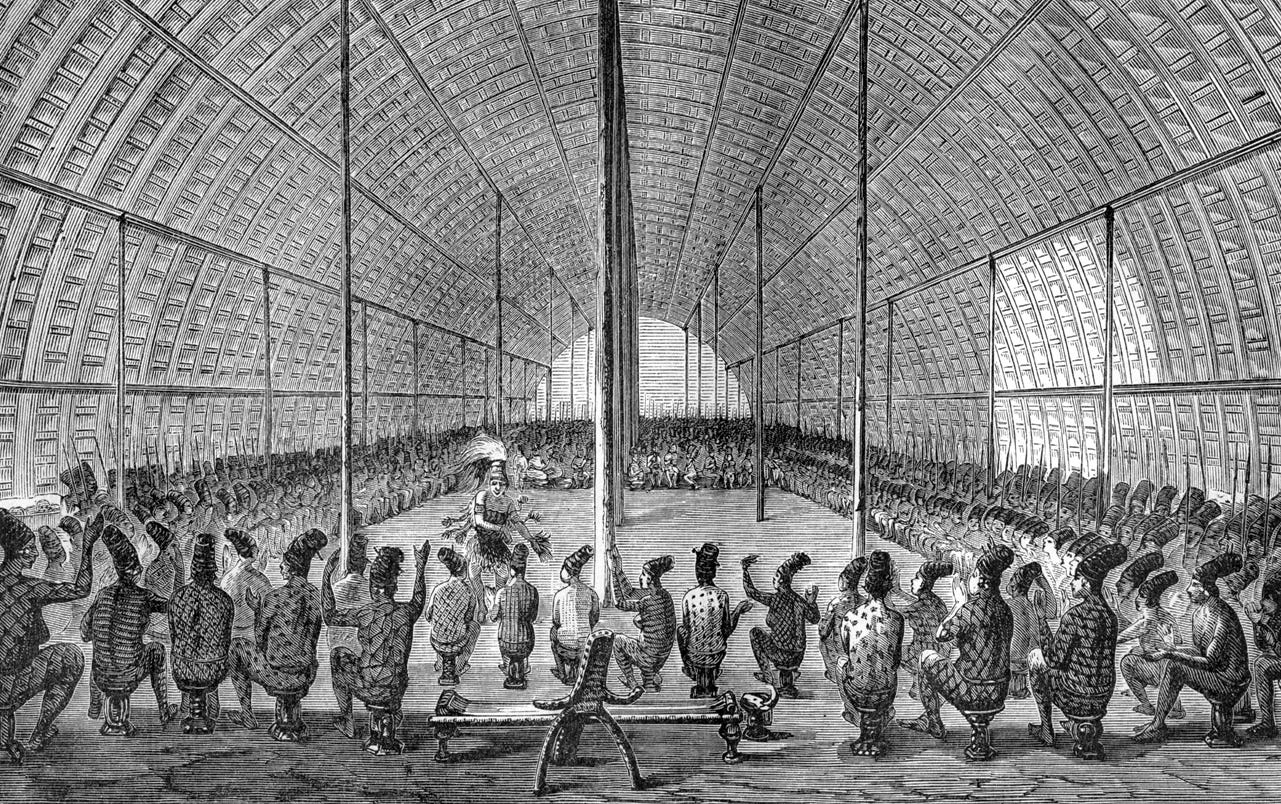

Barth’s account contains one of the earliest descriptions and drawings of the emir’s palace at Yola, and includes some of the distinctive features that are common across the region’s palatial architecture: _**“It has a stately, castle-like appearance, while inside, the hall was rather encroached upon by quadrangular pillars two feet in diameter, which supported the roof, about sixteen feet high, and consisting of a rather heavy entablature of poles in order to withstand the violence of the rains.”**_[29](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-29-167035963)

The historian Mark DeLancey’s study of the palace architecture of Adamawa’s subemirates in Cameroon shows how the different features of elite buildings in the region reflected not just Fulbe construction elements, but also influences from the building styles of the autochtonous Mbum, Dìì, and Péré communities, which were inturn adopted from Hausa and Kanuri architectural forms.[30](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-30-167035963)

The distinctive [style of architecture found in the Hausa city states](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/hausa-urban-architecture-construction?utm_source=publication-search), which was adopted by the Fulbe elites of Sokoto and spread across the empire, had been present in Fomboni among some non-Fulbe groups, such as the Dìì and Mbum of the Adamawa plateau, as well as among early Fulbe arrivals before the establishment of Adamawa. [31](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-31-167035963)

A particularly notable feature in Fomboni’s palatial architecture was the _**sooro**_ —a Hausa/Kanuri word for “a rectangular clay-built house, whether with flat or vaulted roof.” These palaces are typically walled or fenced and have monumental entrances, opening into a series of interior courtyards, halls, and rooms. The ceiling of the sooro is usually supported from within by earthen pillars with a series of arches or wooden beams, and the interior is often adorned with relief sculptures.[32](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-32-167035963)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CALb!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa045cdcb-aee3-4564-9d99-927719869b97_772x552.png)

(left) _**Vaulting in the palace throne room**_, built in the early 1920s by Mohamadou Maiguini at Banyo, Cameroon. Image by Virginia H. DeLancey. (right) _**Vaulted ceiling of the palace at Kano**_, Nigeria.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D4zu!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F735e58d0-204c-45cb-bad9-7da2aaef4d4b_1195x426.png)

_**construction of Hausa vaults in Tahoua, Niger**_, ca. 1928. ANOM

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IO74!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faf7009af-39bb-4467-8331-ea677bdba87d_742x573.png)

_**Vestibule (sifakaré) of the Lamido’s palace at Garoua, Cameroon**_. ca 1932. Quai Branly museum.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!QsKV!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F106e7d97-9f52-4d39-9639-cc41e0204014_752x503.png)

_**Palace entrance in Kontcha, Cameroon**_. Image by Eldridge Mohammadou, ca. 1972

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KZnG!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F49d28f86-bf28-4846-95d5-5ec0432d4969_687x514.png)

_**Entrance to the Sultan's Palace at Rey, Cameroon**_, ca. 1955. Quai Branly

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xryf!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F150cf83d-0548-4c2e-99c6-d4c100772867_955x572.png)

(left)_**Gate within the palace at Rey, Cameroon.**_ ca. 1932. Quai Branly. (right) _**interior of the palace at Garoua, Cameroon**_. ca. 1932. Quai Branly.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_FNW!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1f484240-5de3-4cc7-83b7-ab64a8069ae3_1364x447.png)

(left) _**Interior of Jawleeru Yonnde at Ngaoundéré, Cameroon**_, ca. 1897–1901. National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. (right) _**Plan and interior of the palace entrance at Tignère, Cameroon**_, ca. 1920s–1930s.

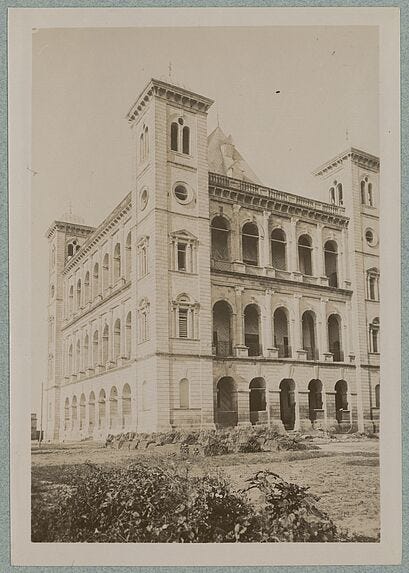

The _sooro_ quickly became an architectural signifier of political power and a prominent mark of power, and as such was the prerogative of only the caliph and the emirs. The construction of a large and majestic _sooro_ at the entrance to the palace at Rey, for example, preceded the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate by 5 years and declared Bouba Ndjidda’s independent status in that land on the eastern periphery of the Fulɓe world.[33](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-33-167035963)

While many of the palaces were destroyed during the colonial invasion, the region’s unique architectural style remained popular among local elites well into the colonial period.

**Decline, collapse, and the effects of colonialism in Adamawa.**

Lawal was succeeded by the _Lamido_ Umaru Sanda (r. 1872-1890), during whose relatively weak reign rebellions by the sub-emirates continued unabated, and some non-Fulbe peoples seized the opportunity to become independent. In the Benue valley, some of the more powerful chiefs among the Batta and Tengelen threw off their allegiance and began to attack ivory caravans. An expedition sent against the Tengelen in 1885 was defeated, underscoring the weakness of the Adamawa forces at the time, which often deserted during battle.[34](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-34-167035963)

The expansion of European commercial interests on the Benue during the late 1880s was initially checked by Sanda, who often banned their ivory trade despite directives from Sokoto to open up the region for trade. Sanda ultimately allowed the establishment of two trading posts of The Royal Niger Company at Ribago and Garua, but none were allowed at the capital Yola.[35](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-35-167035963)

Sanda was succeeded by the _Lamido_ Zubairu (r. 1890-1903,) who inherited all the challenges of his predecessor, including internal rebellions —the largest of which was in 1892, led by the Mahdist claimant Hayat, who was allied with the warlord Rabih. Zubairu's forces were equally less successful against the non-Fulbe subjects, who also rebelled against Yola, and his forces failed to reconquer the Mundang and Margi of the Bazza area on the Nigeria/Cameroon border region.[36](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-36-167035963)

In the 1890s, Yola became the focus of colonial rivalry between the British, French, and Germans during the colonial scramble as each sought to partition the empire of Sokoto before formally occupying it.[37](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-37-167035963)

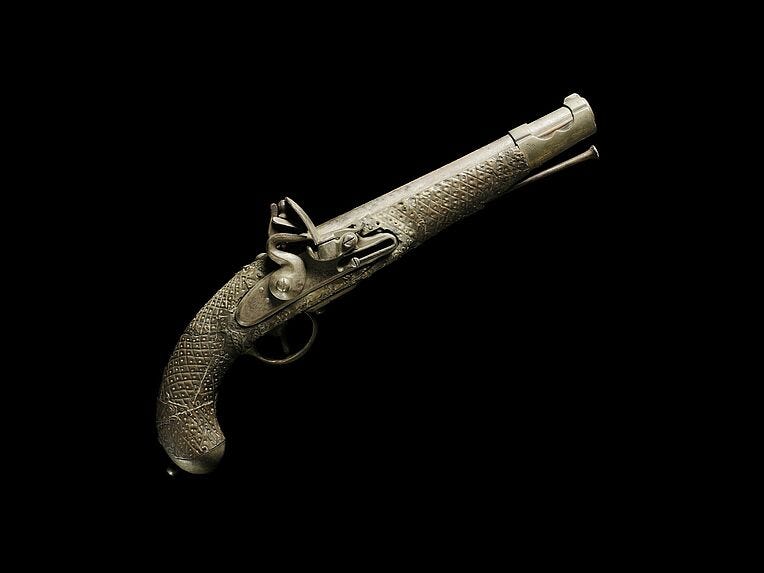

Zubairu initially played off each side in order to acquire firearms, but the aggressive expansion of the Germans in Kamerun forced the southern emirates to adopt a more hostile stance towards the Germans, who promptly sacked Tibati and Ngaoundéré in 1899 and took control of the eastern sub-emirates.[38](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-38-167035963)

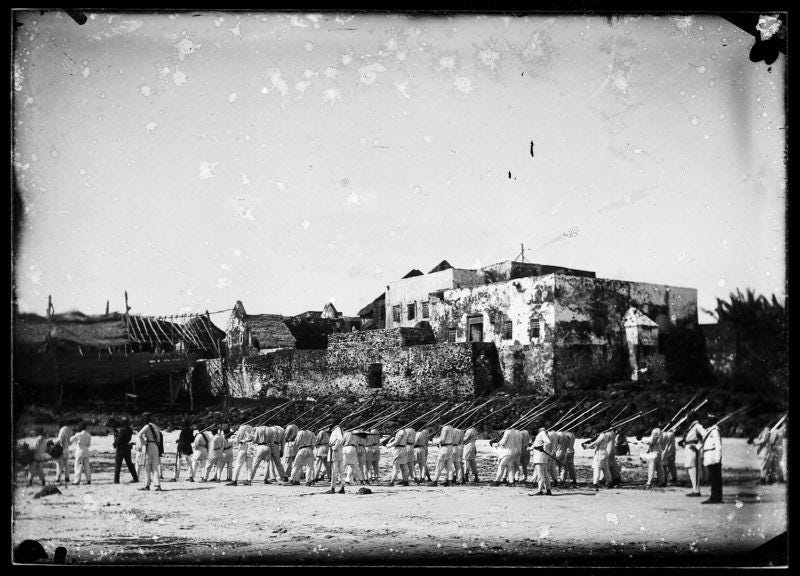

While the defeat of Rabih by the French in 1900 removed Zubairu's main rival, it left him as the only African ruler surrounded by the three colonial powers. Lord Lugard, who took over the activities of the Royal Niger company that same year, sent an expedition to Yola in 1901 which captured the capital and burned its main buildings despite stiff resistance from Zubairu’s riflemen. Zubairu fled the capital and briefly led a guerrilla campaign against the colonialists but ultimately died in 1903, after which the emirate was formally partitioned between colonial Nigeria and Cameroon.[39](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-39-167035963)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K6uo!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc114718b-2fd6-4d86-84e5-e2edfe156d2e_718x490.png)

_**‘The final assault and capture of the palace and mosque at Yola.’**_ Lithograph by Henry Charles Seppings Wright, ca. 1901.

After the demarcation of the Anglo-German boundary, 7/8th of the Adamawa emirate fell on the German side of the colonial boundary in what is today Cameroon. The boundary line between the British and German possessions did not follow the boundaries of the sub-emirates, some of which were also divided. In some extreme cases, such as the metropolis of Yola itself, only the capitals remained under their rulers while the towns and villages were separated from their farmlands and grazing grounds.[40](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-40-167035963)

While it’s often asserted that the colonial partition of Africa separated communities that were previously bound by their ethnic identity, the case of Adamawa and similar pre-colonial states shows that such partition was between heterogeneous communities with a shared political history. This separation profoundly altered the political and social interactions between the various sub-emirates and would play a significant role in shaping the history of modern Cameroon.[41](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-41-167035963)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fEAv!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdebfce2b-d595-4aa6-853d-c4da6005b681_825x576.png)

North Cameroon, _**Ngaounderé Horsemen of the Sultan of Rey Bouba**_. mid-20th century.

**My latest Patreon article explores the history of the Sanussiya order of the Central Sahara, which developed into a vast pan-african anti-colonial resistance that sustained the independence of this region until the end of the First World War.**

**Please subscribe to read more about it here.**

[THE SANUSIYYA MOVEMENT](https://www.patreon.com/posts/131994687?pr=true&forSale=true)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6V4Y!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6618a926-ee68-40f9-b3bd-10eb7ec0cee4_730x1234.png)

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-1-167035963)

Modified by author based on the map of the Sokoto caliphate by Paul. E. Lovejoy and a map of Adamawa’s principal districts and tribes by MZ Njeuma

[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-2-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 37-38

[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-3-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 34-36, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 473

[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-4-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 1, 5-20, Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 25

[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-5-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 17

[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-6-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 20-23

[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-7-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg pg 5

[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-8-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 30-32, 36-39, _on Islam among the Adamawa Fulani_: The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 55-57

[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-9-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 11

[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-10-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 39-42, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 40-43

[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-11-167035963)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 5-12, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 43-49

[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-12-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 2-3, 50-51

[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-13-167035963)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 14-15, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 56-62)

[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-14-167035963)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 19- 24, The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 64-69

[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-15-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey pg 13-14, Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 36-38, War, Power and Society in the Fulanese “Lamidats” of Northern Cameroon: the case of Ngaoundéré in the 19th century by Theodore Takou pg 93-106

[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-16-167035963)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma, pg 58

[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-17-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 75-79

[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-18-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 90-95

[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-19-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 157-240

[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-20-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 243-244

[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-21-167035963)

War, Power and Society in the Fulanese “Lamidats” of Northern Cameroon: the case of Ngaoundéré in the 19th century by Theodore Takou pg 93-106

[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-22-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 96-100

[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-23-167035963)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma pg 37-41,

[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-24-167035963)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 By Heinrich Barth, pg 430, 469

[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-25-167035963)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 By Heinrich Barth, pg 458, 469

[26](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-26-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 306-309)

[27](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-27-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 105-109

[28](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-28-167035963)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 472

[29](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-29-167035963)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth, pg 463

[30](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-30-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey 19-20, 34-64

[31](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-31-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey pg 72

[32](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-32-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 66-91)

[33](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-33-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 75

[34](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-34-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 124-126

[35](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-35-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 134-135

[36](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-36-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 135-138

[37](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-37-167035963)

The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 317-320

[38](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-38-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 139-144, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 321-423

[39](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-39-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 145-148, The Rise and Fall of Fulani Rule in Adamawa, 1809-1901 by MZ Njeuma, pg 424-460

[40](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-40-167035963)

The Lāmīb̳e of Fombina: A Political History of Adamawa, 1809-1901 by Saʹad Abubakar, pg 154

[41](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th#footnote-anchor-41-167035963)

Conquest and Construction: Palace Architecture in Northern Cameroon By Mark DeLancey, pg 79-100, Regional Balance and National Integration in Cameroon: Lessons Learned and the Uncertain Future by Paul Nchoji Nkwi, Francis B. Nyamnjoh

|

[

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5MaD!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7fce441c-4c73-4a4f-b9ae-67696177d157_1338x657.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8fRE!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F07438da9-57fb-4d24-87c6-783ee96905a4_736x545.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xrtP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb605eaa3-8b17-48b9-b35d-cae70949feb8_576x573.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xx0L!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9c7ca74e-da1e-4aa9-a325-5fbf670b6455_889x602.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Rrxp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6a559b8d-37e8-4440-8a46-c350425654a7_827x593.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kNXA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd9ee6490-f0d9-41aa-b28d-177d44cd1ac2_942x459.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!clic!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F620e2911-8eb8-4b54-83b0-068b284d6090_1048x442.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CALb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa045cdcb-aee3-4564-9d99-927719869b97_772x552.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D4zu!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F735e58d0-204c-45cb-bad9-7da2aaef4d4b_1195x426.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IO74!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faf7009af-39bb-4467-8331-ea677bdba87d_742x573.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!QsKV!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F106e7d97-9f52-4d39-9639-cc41e0204014_752x503.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KZnG!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F49d28f86-bf28-4846-95d5-5ec0432d4969_687x514.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xryf!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F150cf83d-0548-4c2e-99c6-d4c100772867_955x572.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_FNW!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1f484240-5de3-4cc7-83b7-ab64a8069ae3_1364x447.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K6uo!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc114718b-2fd6-4d86-84e5-e2edfe156d2e_718x490.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fEAv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdebfce2b-d595-4aa6-853d-c4da6005b681_825x576.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6V4Y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6618a926-ee68-40f9-b3bd-10eb7ec0cee4_730x1234.png"

] |

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-society-and-ethnicity-in-19th

|

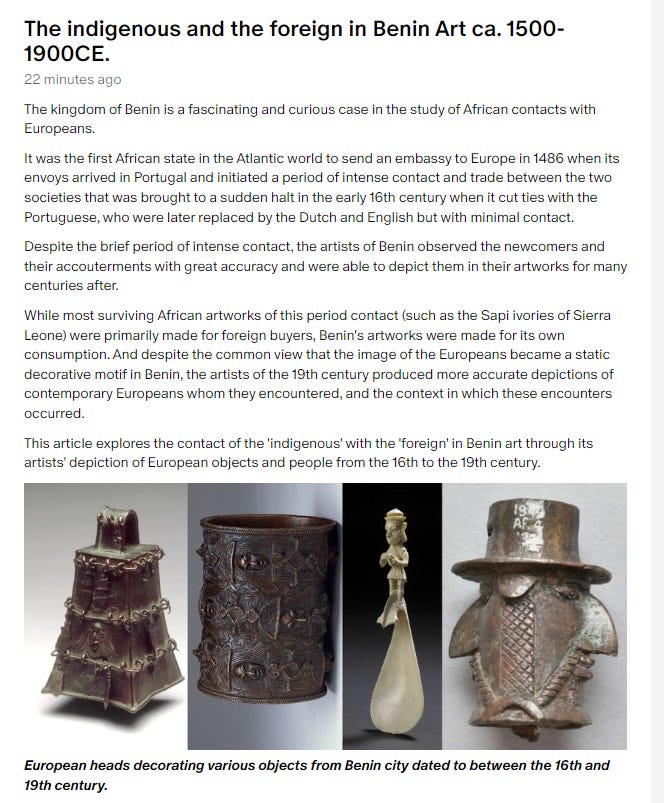

The modern separation of Africa into a “Mediterranean” North and a “Sub-Saharan” South had little basis in the historical geographies and political relationships of the pre-colonial period.

This Hegelian misconception, which is predicated on the belief that the Sahara was an impenetrable barrier, contradicts the historical evidence, which shows that the desert can be likened to an inland sea, facilitating cultural and economic exchanges between ancient societies along its ‘shores’ and within the desert itself.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/historic-links-between-the-maghreb#footnote-1-166517760)

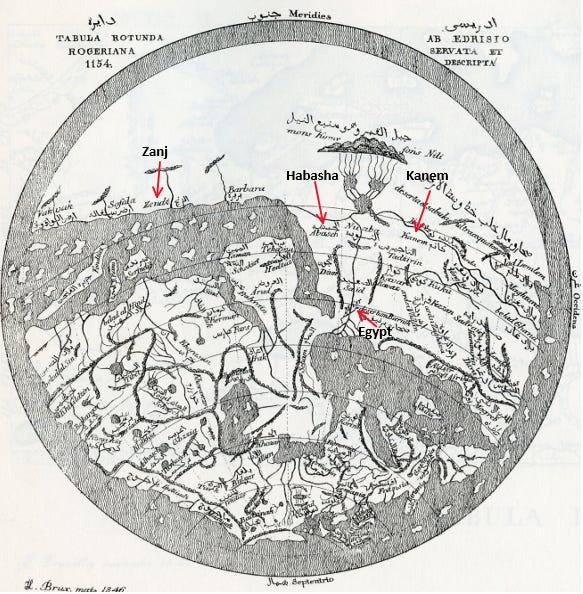

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EzB5!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F52057804-3b66-41f0-b217-f606a5ca803b_1027x561.jpeg)

_**The ancient cities and oases of the Sahara**_. Map by D. J. Mattingly et.al

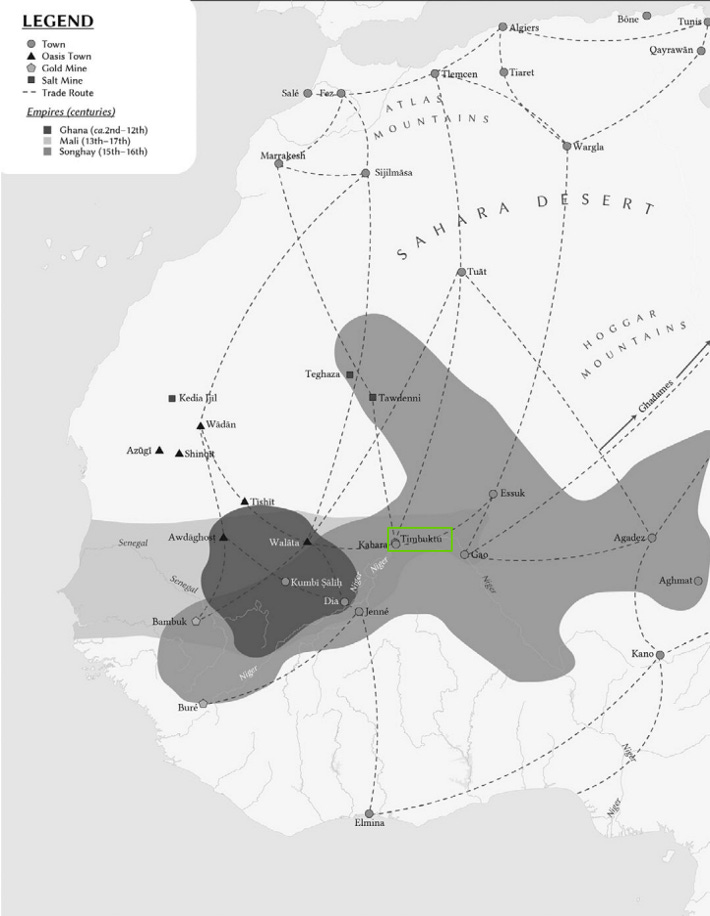

In the western half of the Sahara, the emergence of large kingdoms in what is today Mauritania, Mali, Senegal, and Morocco during the Middle Ages enabled the creation of a broadly similar cultural economy across multiple societies that were interlinked through trade, travel, and Islamic scholarship.

The Almoravid empire (1040-1147), whose founder Yaḥyā ibn Ibrāhīm hailed from what is today southern Mauritania, [was closely allied with the kingdom of Takrur in Senegal](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-building-in-ancient-west-africa#footnote-anchor-35-51075574), which provided [contingents for the empire's conquests into Morocco and Spain](https://www.patreon.com/posts/african-diaspora-82902179).

The Almoravids established close ties with West African states such as the Ghana empire (700-1250), and the enigmatic kingdom of Zafun, about whose king the Almoravids were said to [“acknowledge his superiority over them.”](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/state-building-in-ancient-west-africa#footnote-anchor-60-51075574%20.)

Their successors, such as the Almohads (1121-1269) and the Marinids (1244-1465), continued in this tradition, enabling the career of celebrated scholars like Ibrahim Al-Kanemi (d. 1211), and the exchange of [several diplomatic missions with medieval Mali in 1337, 1348, 1351, and 1361.](https://www.patreon.com/posts/107625792)

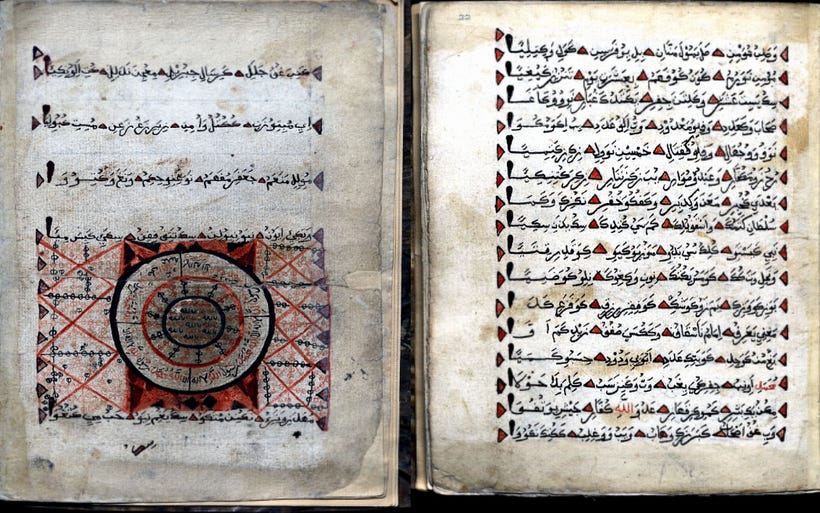

By the close of the Middle Ages, scholarly exchanges between the intellectual communities of Timbuktu and Djenne (Mali) with those in Fez and Marrakesh (Morocco), as well as the expansion of trade between Sijilmasa (Morocco), Taghaza (Mali), and Walata (Mauritania) resulted in more direct links between both ends of the Sahara.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VL84!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1f07dc9-a1b9-4994-bd8c-56574383d10b_641x425.png)

_**Palm grove of Tafilalet in Sijilmassa, Morocco.**_ The oasis of Sijilmasa was a crucial hub in the trade route between medieval Ghana and Morocco.

The competitive political landscape engendered by these long-distance exchanges facilitated the expansion and inevitable [clash between the Songhai and Saadian empires](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/morocco-songhai-bornu-and-the-quest), which ended with the latter’s brief occupation of Timbuktu and Djenne in the 17th century. Forced to withdraw due to local resistance, the Moroccans retained some ties with [the old towns of Mauritania in the 18th century](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-south-western-saharan).

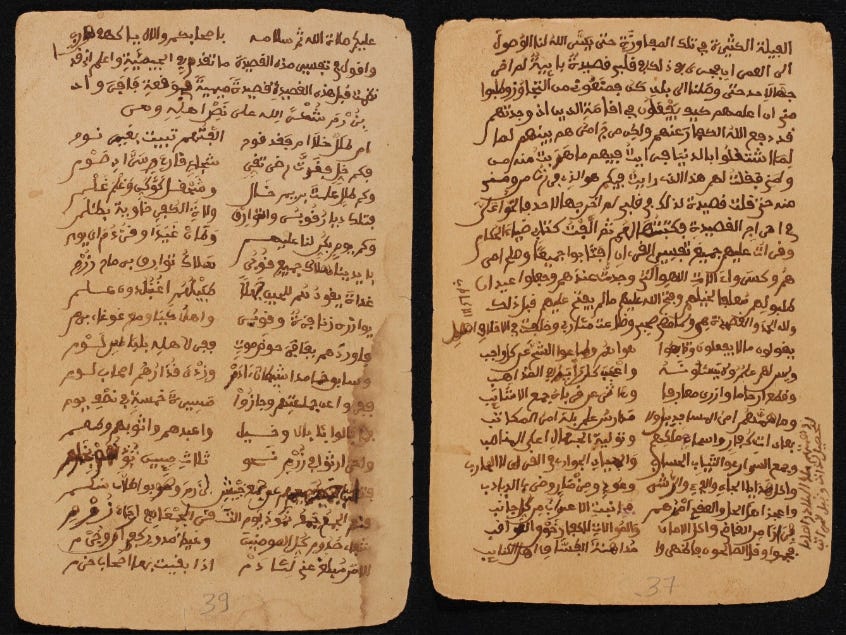

However, the old scholarly and economic links between the two regions continued to flourish.

Movements such as the Tijaniyya attracted prominent scholars across the region during the 19th century, and its main _**zawiya**_ (sufi lodge) in Fez remains [an important cultural link between communities in Senegal and Morocco](https://www.patreon.com/posts/107625792), and today forms the lynchpin of the two countries' religious and political diplomacy.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Zl2-!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2f0585dd-b6e0-4a90-a56c-b109c97b201d_820x398.png)

_**Zawiya of Ahmad al-Tijânî in Fez, Morocco**_. _This Sufi lodge is a major pilgrimage site for Tijani scholars from Senegal and Mali._

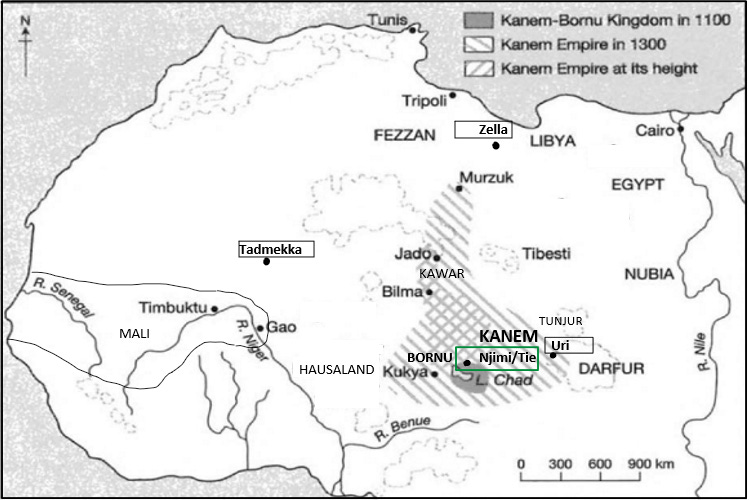

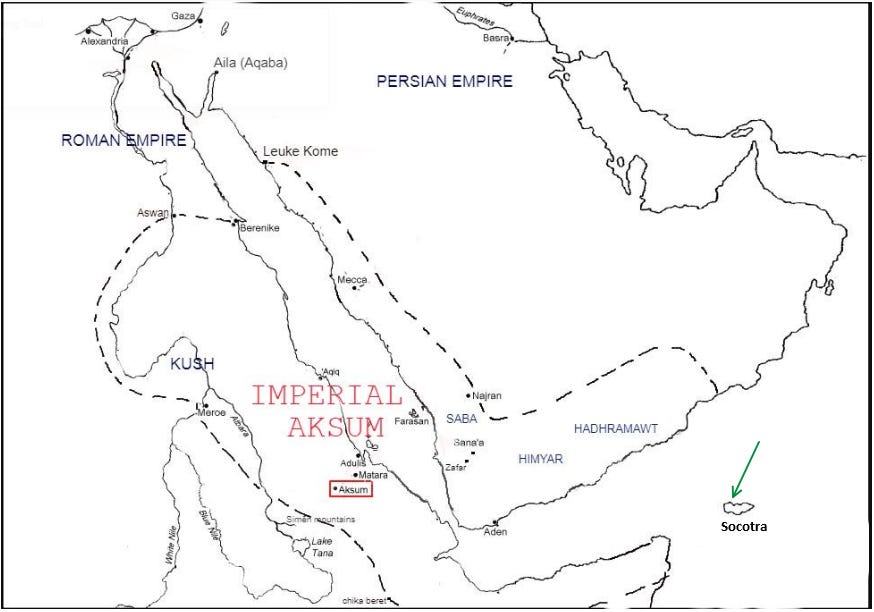

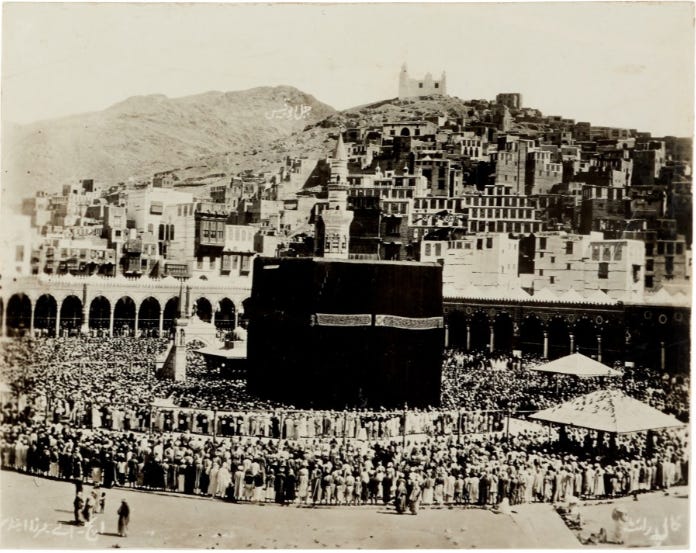

In the central regions of the Sahara, [the empire of medieval Kānem (800-1472)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-forgotten-african-empire-the-history) in Chad and [the Oasis towns of Kawar in eastern Niger](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/an-african-civilization-in-the-heart) maintained cultural and economic ties with societies in the Fezzan (Southern Libya) and the mediterranean coast since the middle ages.

After the conquest of the Fezzan by medieval Kanem in the 13th century, diplomatic missions from the latter were sent to the Hafsid court in Tunis in 1257. Kanem's successor, the empire of Bornu, continued this tradition, sending embassies to neighbouring Tripoli in 1526, 1535, 1551, 1574, 1581, and 1586.

Diasporic communities were established in Tunis and Tripoli, which facilitated [trade and diplomatic exchanges between Bornu and the Ottomans of Tripoli](https://www.patreon.com/posts/first-guns-and-84319870) during the 17th century, as well as the movement of pilgrims and scholars, some of whom settled in the oases of Murquz and Kufra in Libya.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6Ddw!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F89a796b9-11e3-495a-a76c-8dd3c7dd417d_673x458.png)

_**View of Murzuk, Libya. ca. 1890**_. GettyImages. _Some of the streets of Murzuq still bear Kanembu and Kanuri names, and the town was the birthplace of the Bornu ruler al-Kanemi_

Historical ties between the Maghreb and West Africa were thus unimpeded by the Sahara. As previously explored in my essay on [the colonial myth of Sub-Saharan Africa](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-colonial-myth-of-sub-saharan), this separation was never a historical reality for the people living in either region, but is instead a more recent colonial construct with a fabricated history.

This is especially evident in the expansion of the political-religious movement known as the Sanusiyya, a sufi order which emerged in eastern Libya during the 19th century.

The Sanusiyya, which was founded by a scholar from Mostaganem in Algeria, attracted scholars from across Africa and Arabia. Its adherents established numerous _**zawiya**_ s in Tunisia, Egypt, and Algeria, as well as in; Kawar and Zinder (Niger); Kano (Nigeria); Wadai and Kanem (Chad); and Darfur (Sudan).

The order provided a unified identity among the lineage-based acephalous societies of the Sahara, as every member considered themselves to be Sanusi, rather than Teda, Tuareg, or Arab. Scholars from across the central Sahara converged at its capital, Jaghbub, which was described as the _**“Oxford of the Sahara.”**_

During the colonial onslaught at the turn of the 20th century, Sanusi lodges became rallying points for anti-colonial resistance, providing modern firearms to the armies of Wadai and Darfur, and sustaining the independence of this region until the end of the First World War. The Sanusi-dominated central Sahara was thus the last region on the continent to fall under colonial control.

**The history of the Sanusiyya and their anti-colonial resistance is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here.**

[THE SANUSIYYA MOVEMENT](https://www.patreon.com/posts/131994687?pr=true&forSale=true)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6V4Y!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6618a926-ee68-40f9-b3bd-10eb7ec0cee4_730x1234.png)

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/historic-links-between-the-maghreb#footnote-anchor-1-166517760)

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly, Mobile Technologies in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by C. N. Duckworth, A. Cuénod, D. J. Mattingly, Burials, Migration and Identity in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by M. C. Gatto, D. J. Mattingly, N. Ray, M. Sterry

|

[

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EzB5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F52057804-3b66-41f0-b217-f606a5ca803b_1027x561.jpeg",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VL84!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1f07dc9-a1b9-4994-bd8c-56574383d10b_641x425.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Zl2-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2f0585dd-b6e0-4a90-a56c-b109c97b201d_820x398.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6Ddw!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F89a796b9-11e3-495a-a76c-8dd3c7dd417d_673x458.png",

"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6V4Y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6618a926-ee68-40f9-b3bd-10eb7ec0cee4_730x1234.png"

] |

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/historic-links-between-the-maghreb

|

Pre-colonial Africa was home to some of the oldest and most diverse equestrian societies in the world. From the [ancient horsemen of Kush](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-knights-of-ancient-nubia-horsemen) to the [medieval Knights of West Africa](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/knights-of-the-sahara-a-history-of) and [the cavaliers of Southern Africa](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-horses-in-the-southern?utm_source=publication-search), horses have played a significant role in shaping the continent's political and social history.

In Ethiopia, the introduction of the horse during the Middle Ages profoundly influenced the structure of military systems in the societies of the northern Horn of Africa, resulting in the creation of some of Africa's largest and most powerful cavalries.

As distinctive symbols of social status, horses were central to the aristocratic image of rulers and elites in medieval Ethiopia, while as weapons of war, they changed the face of battle and the region’s social landscape. Today, the horse remains the most culturally respected and highly valued domestic animal in Ethiopia, and the country is home to Africa's largest horse population.

This article explores the history of the horse in the kingdoms and empires of Ethiopia since the Middle Ages, and the development of the country’s diverse equestrian traditions.

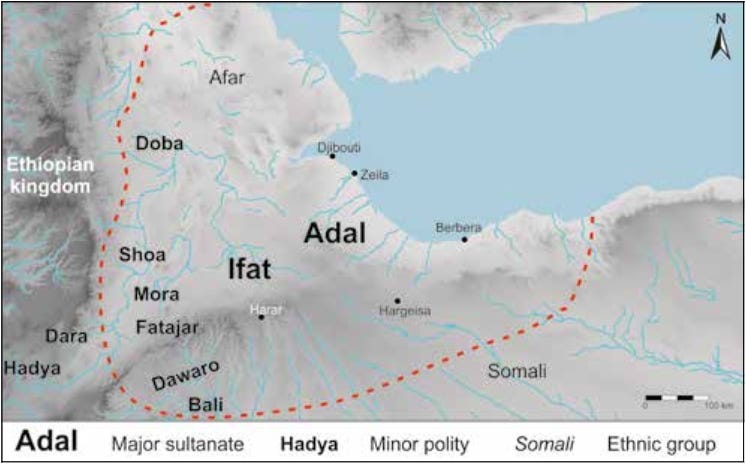

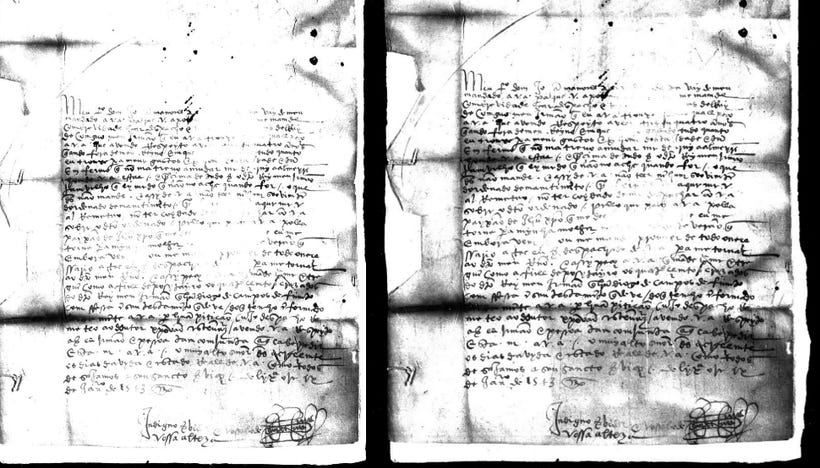

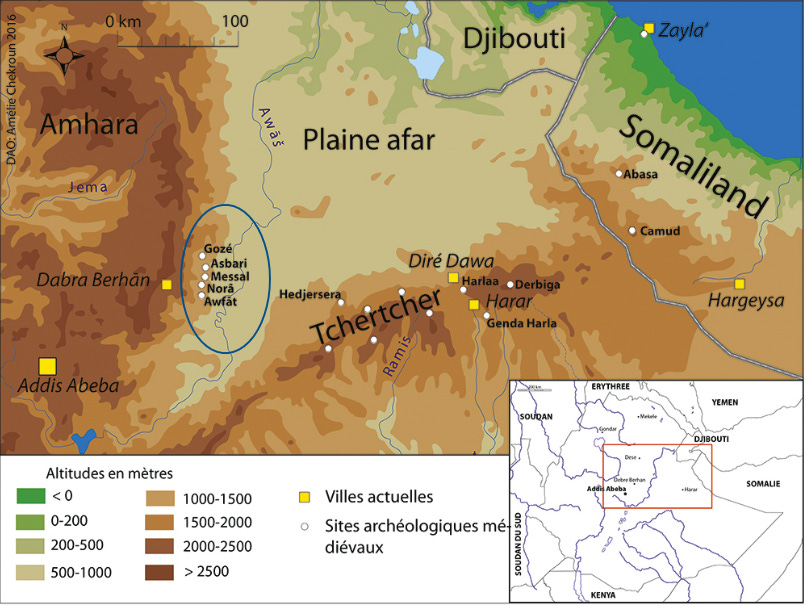

_**Map showing some of the societies in northeastern Africa at the end of the 16th century.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-1-165941643)**_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lhVZ!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcfabc53f-aa8a-4748-bfc3-f70cb5bb35de_613x685.png)

**Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

**Historical background: horses and cavalries in Ethiopia until the 16th century**

The first equids used by the ancient societies of north-east Africa were donkeys, which were domesticated in the region around 2500BC, while horses were introduced later by 1500BC.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-2-165941643)

A few equid remains are represented in small numbers in the faunal assemblages of Aksum, but their exact identification remains problematic since none of the archaeozoological specimens has been precisely identified at the species level. According to the archaeologist David Phillipson, there is no convincing evidence that horses were exploited in the Aksumite kingdom.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-3-165941643)

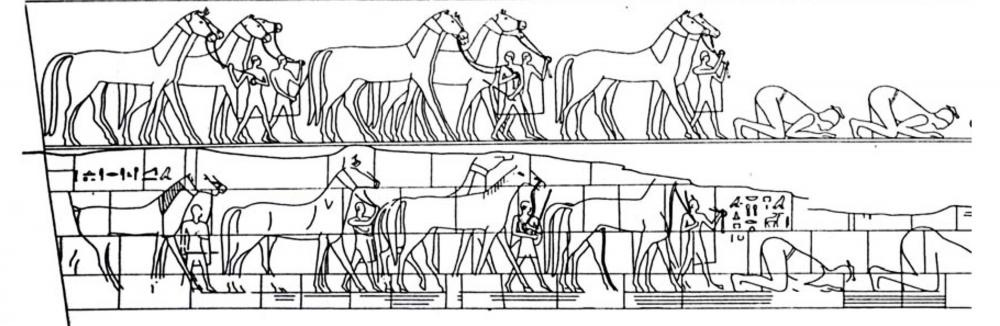

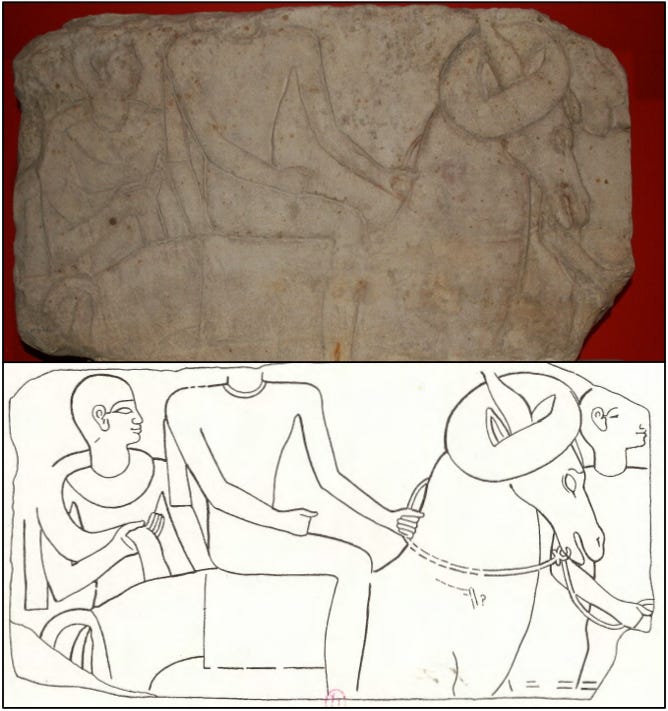

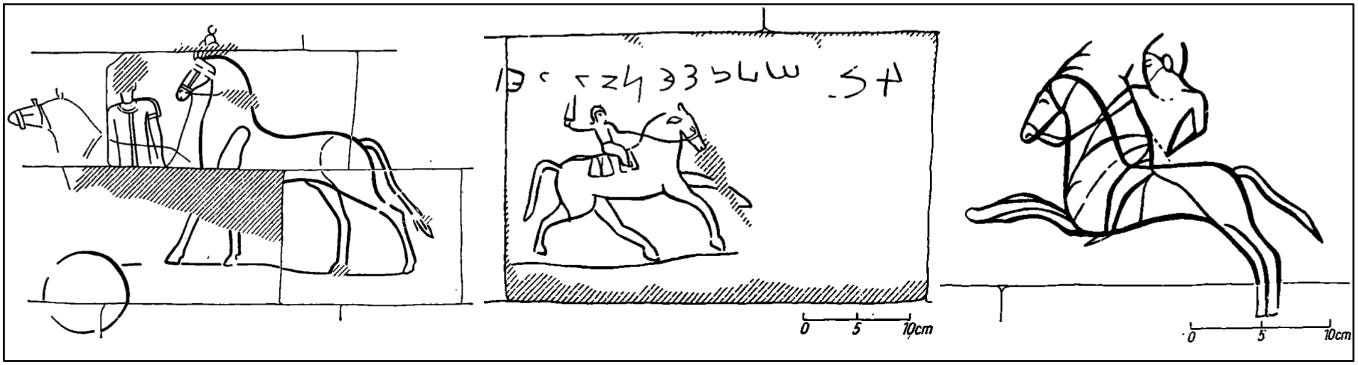

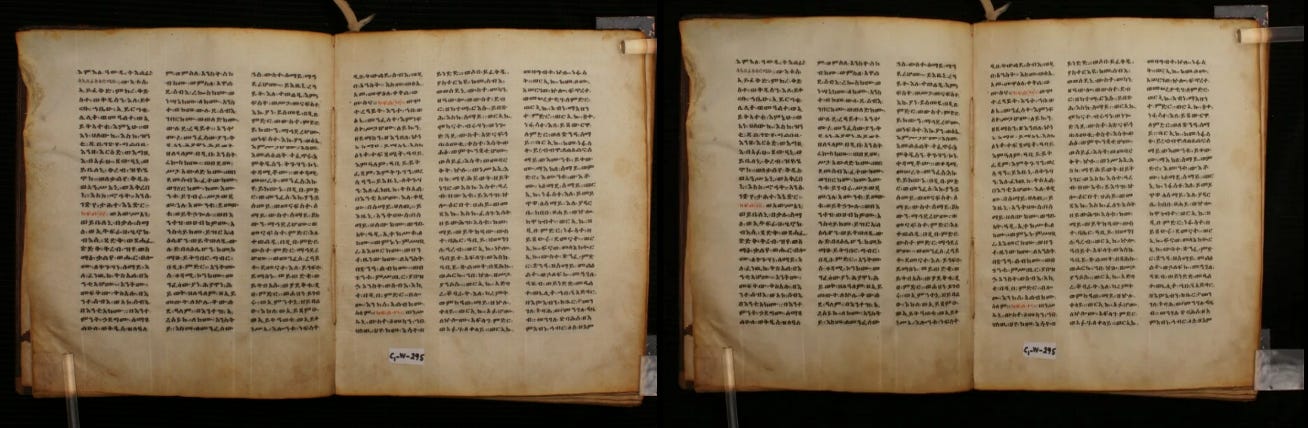

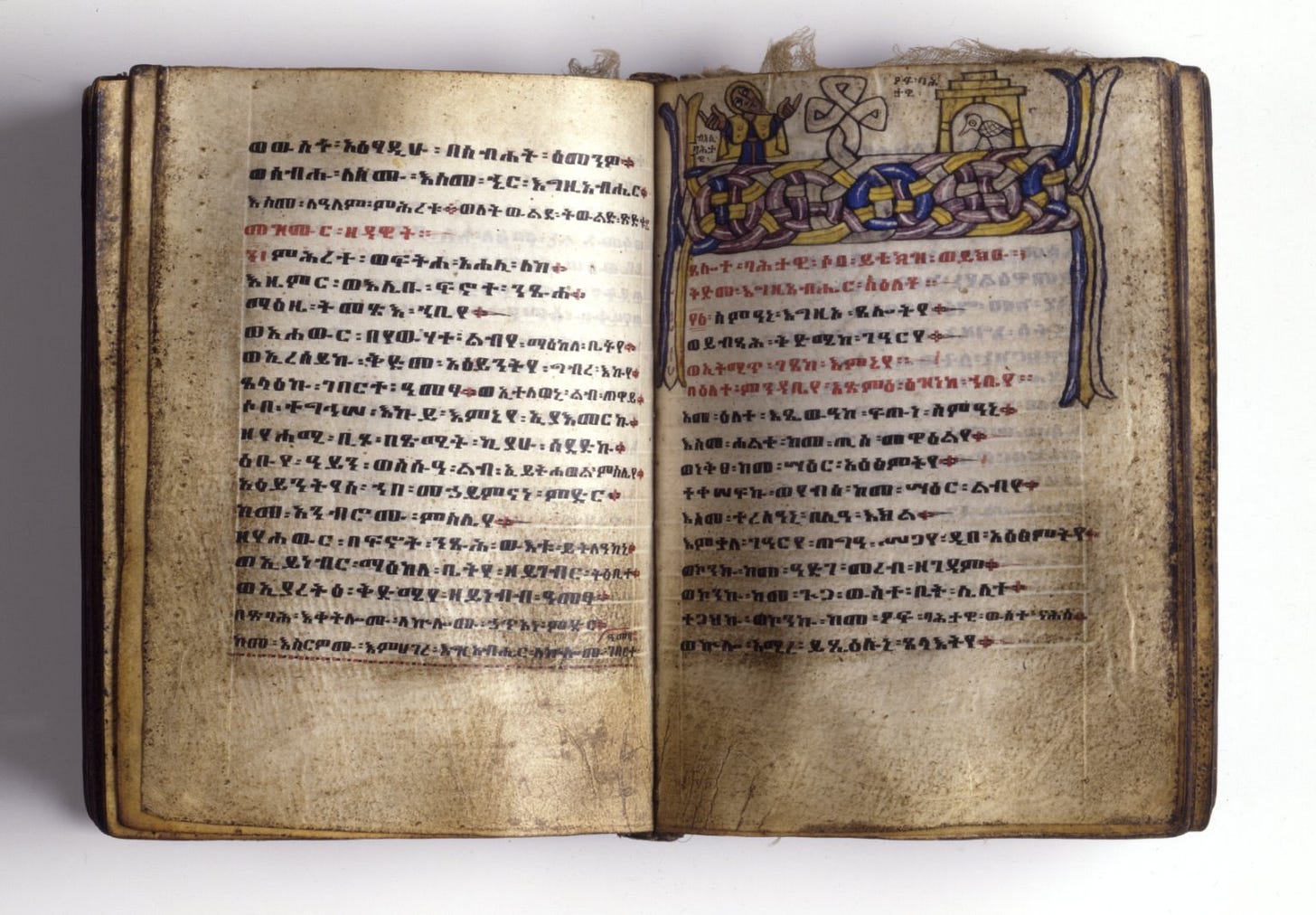

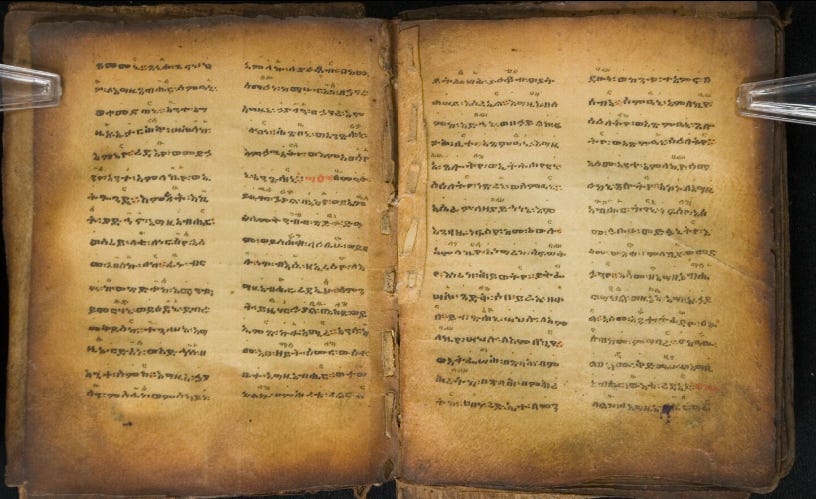

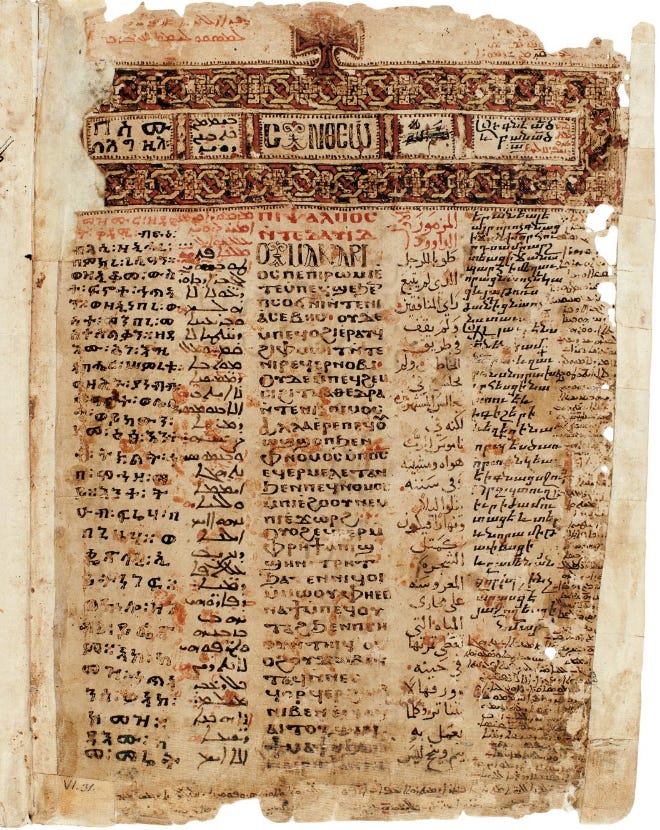

Horses first appear in Ethiopia's historical record in the late Middle Ages, during the [Zagwe period (ca. 1150-1270CE)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/constructing-a-global-monument-in?utm_source=publication-search). There are a handful of representations of horses on the western porch of Betä Maryam church of Lalibäla, consisting of sculptures in low relief showing horsemen hunting real and mythological animals.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-4-165941643) Envoys from the Egyptian Coptic patriarch during the reign of Lalibela mention that the Zagwe monarch had a large army, consisting of an estimated 60,000 mounted soldiers, not counting the numerous servants who followed them.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-5-165941643)

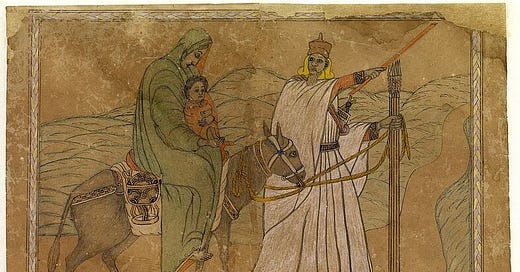

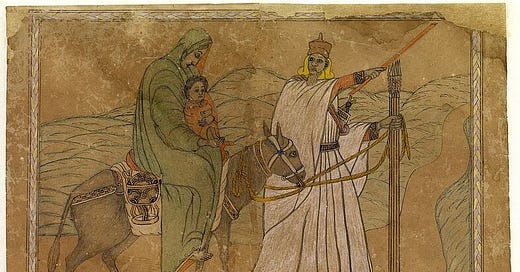

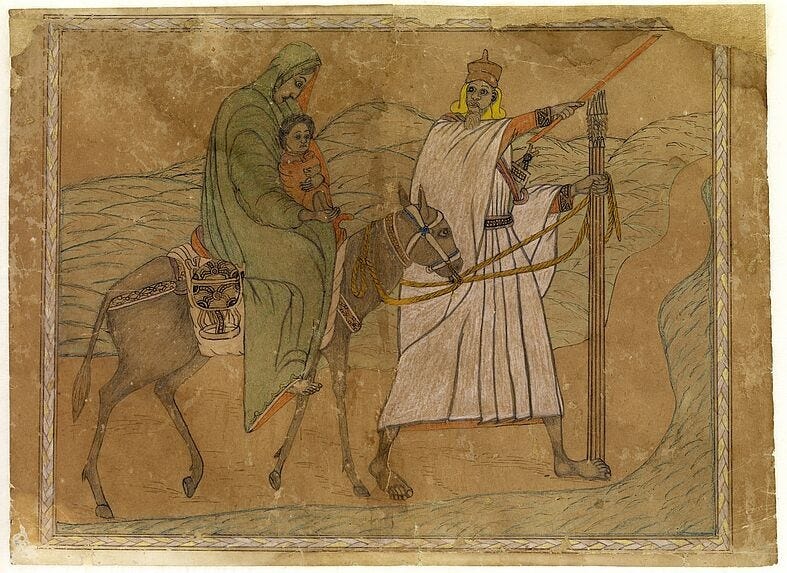

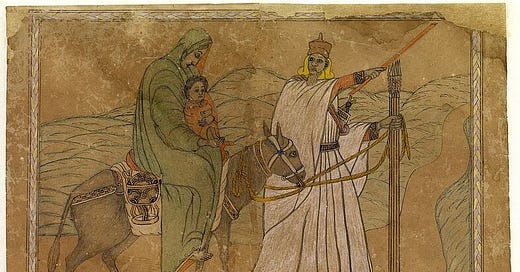

In the area east and south of Lalibäla, three churches display on their walls paintings associated with Yǝkunno Amlak (r. 1270–1285), who overthrew the Zagwe rulers and founded the Solomonic dynasty of the Christian kingdom. One of the paintings in the vestibule of the rock-hewn church of Gännätä Maryam depicts a certain prince named Kwəleṣewon on a horse, in a style of royal iconography that would become common during later periods.[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-6-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pjM8!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc865b9b0-a67c-46f8-af81-9bb3fd50a8b1_731x562.png)

(left) _**Horse tracks on the wall of Biete Giyorgis church**_, Lalibela, Ethiopia. Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. The church is dated to the 14th-15th century. (right) _**Mural depicting the Wise Virgins (upper register) and prince Kwəleṣewon with his mother Təhrəyännä Maryam (lower register)**_, church of Gännätä Maryam ca. 1270–85. image by Claire Bosc-Tiessé.

A letter from Yǝkunno Amlak to the Mamluk Egyptian Sultan Baybars (r. 1260-77), mentions that the large army of the Ethiopian monarch included a hundred thousand Muslim cavaliers. The above estimates of the cavalries of king Lalibela and Yǝkunno Amlak were certainly exaggerated, but indicate that mounted soldiers were already part of the military systems of societies in the northern Horn of Africa by the 13th century.[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-7-165941643)

By the reign of ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon, the Solomonid monarchs of Ethiopia had built up a large cavalry force, mostly raised from the provinces of Goǧǧam and Damot. The King's chronicle mentions that in response to a rebellion in 1332, _**“He sent other contingents called Damot, Seqelt, Gonder, and Hadya (consisting of) mounted soldiers and footmen and well trained in warfare...”**_[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-8-165941643)

Mamluk records from the early 15th century, which describe the activities of the Persian merchant called al-Tabrīzī, mention horses and arms among the trade items exported from Egypt to Ethiopia through the Muslim kingdoms of the region.[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-9-165941643)

The account of Ibn Fadl Allah, written between 1342 and 1349, lists the armed forces of Ethiopia’s Muslim sultanates: Hadya, ‘the most powerful of all’, had 40,000 horsemen and ‘an immense number of infantry’. Ifat and Dawaro had each about 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers, Bali 18,000 horsemen and a mass of footmen, Arababni nearly 10,000 cavalry and ‘very numerous’ infantry, Sharkha 3,000 horsemen and at least twice that number of infantry, and Dara, the weakest province, 2,000 horse and as many in the infantry.[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-10-165941643)

However, these figures were likely inflated since internal accounts and accounts by later visitors to the region provide much lower estimates, especially for the cavalries of the Adal empire, which united these various Muslim polities in the 15th century and imported horses from Yemen and Arabia.

During the Adal invasion of Ethiopia in 1529, at the decisive battle of ShemberaKure, the Adal general Imam Ahmad Gran had an army of 560 horsemen and 12,000-foot soldiers, while the Ethiopian army was made up of 16,000 horsemen and more than 200,000 infantry; according to the Muslim chronicler of the wars. Ethiopian accounts, on the other hand, put the invading forces at 300 horsemen and very few infantry, and their own forces at over 3,000 horsemen and ‘innumerable’ foot-men.[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-11-165941643)

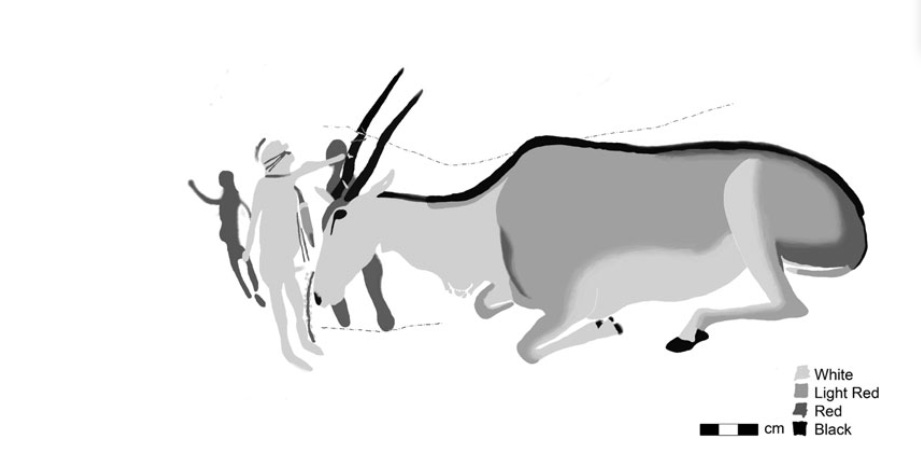

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!XNxb!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7b70502a-7346-4a3a-be3c-a74c1754872c_782x598.png)

(left) _**Abyssinian Warriors**_ ca. 1930. Mary Evans Picture Library. (right) _**Horseman from Harar**_. ca. 1920, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

As for the cavalries forces of the southern regions, the 1592 account of Abba Baḥrǝy notes that the Oromo ruler luba mesele (Michelle Gada, r. 1554-1562) _**“began the custom of riding horses and mules, which the [Oromo] had not done previously.”**_ However, it’s likely that the Oromo began using horses much earlier than this, but hadn't deployed them in battle since their early campaigns mostly consisted of nighttime guerrilla attacks, which made horses less important.[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-12-165941643)

Oromo moieties of the Borana and Barentu quickly formed cavalry units, which enabled them to rapidly expand their areas of influence over much of the horse-rich southern half of the territories controlled by [the Gondarine kingdom of Ethiopia](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/global-encounters-and-a-century-of?utm_source=publication-search) as well as parts of the Muslim kingdom of Adal.[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-13-165941643) According to Pedro Páez, after the Oromo attacked Gojjam, Sarsa Dengel thought it best to excuse the tribute of 3,000 so that the inhabitants of Gojjam could use the horses to defend themselves.[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-14-165941643)

By the close of the 16th century, most of the armies of the northern horn of Africa had large cavalry units.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BMrc!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F332a266f-7535-47f2-b99b-d8629a596126_738x471.png)

_**St George slaying dragon next to the Madonna and Child**_, Fresco from the 18th-century church of Debre Birhan Selassie Church, Gondar, Amhara, Ethiopia.

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

**Horse trade and breeding in Ethiopia from the Middle Ages to the 19th century**

Historical evidence indicates that Ethiopia was both an exporter and importer of horses since the middle ages.

A Ge'ez medieval work describing the 14th century period, mentions that Ethiopian Muslim merchants _**“did business in India, Egypt, and among the people of Greece with the money of the King. He gave them ivory, and excellent horses from Shewa... and these Muslims...went to Egypt, Greece, and Rome and exchanged them for very rich damasks adorned with green and scarlet stones and with the leaves of red gold, which they brought to the king.”**_[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-15-165941643)

The coastal towns of [Zeila](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-zeila-zayla) and Berbera in Somaliland, which served as the main outlet of Ethiopian trade during the Middle Ages, were also renowned for their horse exports. In his 14th-century account, Ibn Said described Zeila as an export center for captives and horses from Abyssinia, while Barbosa in the 16th century describes Zeila as ‘a well-built place’ with ‘many horses.’[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-16-165941643)

Similarly, the port of Berbera was renowned also for its horses which enjoyed a great reputation among the Arabs; the Arab writer Imrolkais emphasizes the quality of the local horses in telling the imaginary story of a noble steed from there that journeyed from the Roman Empire to Arabia. The account of the portuguese Tome Pires, which describes the period from 1512 to 1515, mentions that _**“The principal Abyssinian merchandise were gold, ivory, horses, slaves, and foodstuffs”**_ exported through Zeila and Berbera.[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-17-165941643)

Horses were part of the tribute levied on some Ethiopian provinces, especially those in the southwest such as Gojjam. One of the Amharic royal songs in honor of the Emperor Yǝsḥaq (r. 1414–29) lists the southern provinces with their tribute in kind: gold, horses, cotton, etc. Portuguese accounts from the 16th century also mention that the tribute from Gojjam amounted to 3000 mules, 3000 horses, and 3000 large cotton garments.[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-18-165941643)

The same accounts also mention that horses were received as tribute from Tigray, but many of these appear to have been imported from Egypt and Arabia and were said to be larger than those from Gojjam, implying that the latter were local breeds. The chronicle of Emperor Sartsa Dengel (r. 1563-1597), also notes that the tribute of the _Bahr Negash_ (governor of the coastal region) was composed of large numbers of imported silks and cloth, china ware, and excellent horses.[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-19-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!OxRV!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2870c40c-678b-4703-8975-bd19dd23fc32_667x416.png)

_**Ethiopian rider**_, illustration by Charles-Xavier Rochet d'Héricourt, ca. 1841.

The 16th-century Portuguese traveler Francesco Alvares also mentions that _**“many lords breed horses from the mares they get from Egypt in their stables.”**_[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-20-165941643) 17th-century Portuguese accounts mention that the best of the imported breeds were bought in the hundreds from the kingdom of Dequin, located between Ethiopia and the Funj kingdom of Sennar: these were the famous [Dongola horses](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/knights-of-the-sahara-a-history-of#footnote-anchor-20-53158329) that were exported across west Africa. (James Bruce mentions that Dongola horses were about **16.5 hands** tall). Later accounts from the 17th century note that these breeds were crossed with horses from Tigray and Serae (in Eritrea) to supply the Emperor's stables.[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-21-165941643)

Pedro Páez 1622 account mentions that large horses imported from Dequin (in Sudan) didn’t last long in Ethiopia _**“because they develop sores on their feet, from which they die. The other horses in the empire are commonly small but strong and run fast”**_ and that disputes between the two kingdoms often threatened the lucrative horse trade.[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-22-165941643) It is thus likely that the crossbreeding mentioned above was in response to this challenge. Additionally, the breakdown of trade between Ethiopia and the Funj kingdom (which was the suzerain of Dequin) in the 18th century forced the Ethiopians to breed their own horses in the less-than-ideal conditions of the highlands.[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-23-165941643)

In the 18th century, the regions of Damot and Gojjam were still an important source of horses and horsemen for the Christian kingdom. Internal markets for horses emerged in several trading settlements such as Makina in Lasta, Sanka in Yeju, Cäcaho in Bagémder, Yefag in Dembya, Gui in Gojam, and Bollo-Worké in Shewa.[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-24-165941643)

During this period, horses were included among both the exports and imports to the Muslim kingdoms of Sudan, especially through the border town of Matemma. This was because the Sudanese region of Barca, east Sennar, and Dongola produced fine horses much sought after in Ethiopia for breeding purposes, while the Ethiopian horses were much cheaper than those of the Sudan and were hence in considerable demand across the frontier.[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-25-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ns_-!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1442430-ec9b-4571-90b1-867e3bff6a06_1463x956.jpeg)

_**Abyssinian troops in the field**_. image from "Voyage en Abyssinie", 1839-1843, by Charlemagne Theophile Lefebvre, Ethiopia.

Ethiopian horses were also exported to the Red Sea region, ultimately destined for markets in the western Indian Ocean. An estimated 150 to 200 horses were sold in the market of Galabat, which were then exported through the Red Sea port of Suakin. Merchants from [the city of Gondar](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-complete-history-of-gondar-africas?utm_source=publication-search) also traveled to the port town of Berbera in Somaliland, to export horses, ivory, and captives, which were exchanged for cotton cloths and Indian goods.[26](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-26-165941643)

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the region of Wallo and Agaw Meder in Gojjam were major centers of horse breeding. The region of Agaw Meder in Gojjam was also noted for its production of pack animals. The inhabitants of Agaw Meder bred mare horses and donkey stallions, producing plenty of excellent mules and ponies. In the early 20th century horses of Agaw Meder were in high demand by government officials in the British Sudan, who used them to patrol the frontier.[27](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-27-165941643)

Today, there are eight different breeds of horses in Ethiopia: Abyssinian, Bale, Boran, Horro, Kafa, Ogaden/Wilwal, Selale, and the Kundido feral horse, with a probable ninth breed known as the Gesha horse. Ethiopian horses have a mean height of **12-13 hands**, making them smaller than those in Lesotho and West Africa (13-14 hands), and Sudan (14-17 hands). The tallest Ethiopian breed is the Selale horse —also known as the Oromo horse, which is used as a riding horse. The rest of the breeds serve multiple functions, typically in agricultural work and rural transport.[28](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-28-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uTdE!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4a02e9b8-a7aa-4160-8a04-f7a747c38c43_1015x619.png)

_**Hammel; the horse of emperor Tewodros II that was captured by the British after the battle of Magdala in 1868**_

**Cavalry warfare in medieval and early modern Ethiopia**

The core of Ethiopia's army, as in medieval Europe, was composed of horsemen.

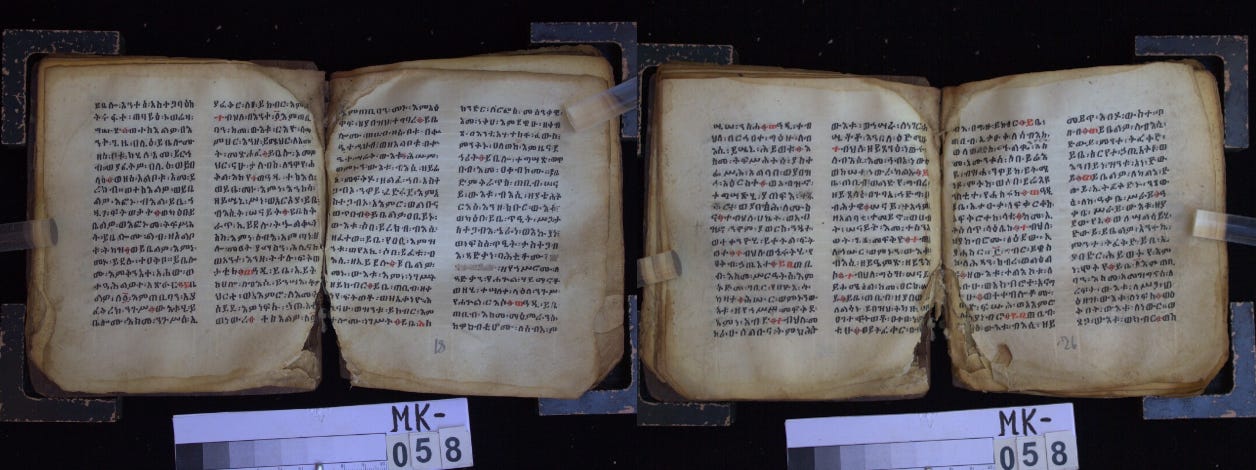

Fighting was for the most part conducted with considerable chivalry. Descriptions of Ethiopian battles in the early 19th century (*****between culturally similar regions) mention that exchanges of civilities would constantly take place between hostile camps, messengers were respected, and prisoners were _**“generally well treated, if of any rank, even with courtesy.”**_ During the actual combat, _**“the horsemen would charge in large or small numbers when and where they thought fit.”**_ Battles were decided within a few hours, and the victors often took loot which included the enemy's horses.[29](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-29-165941643)

A separate cavalry tradition was developed by the Oromo who organized cavalry formations and cultivated vital skills through frequent drilling. Young men grew up practicing throwing spears as well as riding horses in order to become formidable horsemen. Unlike the armies of the Solomonids, however, the Oromo cavalries were highly mobile and relied on guerrilla tactics in combat. According to a 17th-century Portuguese account:

_**“As soon as the [Oromo] perceive an enemy comes on with a powerful army they retire to the farther parts of the country, with all their cattle, the Abyssinians must of necessity either turn back or perish. This is an odd way of making war wherein by flying they overcome the conquerors; and without drawing sword oblige them to encounter with hunger, which is an invincible enemy.”**_[30](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-30-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Gpwj!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F46de780d-aeb3-44b1-ad29-45e355770623_600x370.png)

_**‘Cavalry going into battle, with spears and shields’**_ ca. 1721-c1730. From the ‘Nagara Maryam’ manuscript. Heritage Images

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gpkw!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F449a611b-47b3-408d-aeab-1f0809afa999_736x457.png)

_**‘Fit Aurari Zogo attacking a foot soldier.’**_ Tigray, Ethiopia. ca. 1809. Engraving by Henry Salt.

Emperor Susenyos (r. 1607-1632), who had been raised among the Oromo, quickly adopted their mode of fighting and used it to great effect against internal enemies and the Oromo cavalries, some of whom he allied with and integrated into his own forces. Susenyos and his successors were however unable to gain a decisive advantage over the Oromo cavalries, who in the 18th century, managed to establish strong polities in regions like Wallo that were defended by powerful armies with up to 50,000 horsemen.[31](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-31-165941643)

The horse-riding Awi Agaw groups, who lived in the Gojjam region, also raised large armies of horsemen who battled with the Gondarine monarchs of the Christian Kingdom and the Oromo cavalries during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Scottish traveler James Bruce mentions lineages of the ‘Agows’ such as the _**“Zeegam and Quaquera, the first of which, from its power arising from the populous state of the country, and the number of horses it breeds, seems to have no reason to fear the irregular invasions of [the Oromo]”**_[32](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-32-165941643)

In the mid-16th century, Galawdewos’ army consisted of only 20,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, but by the 17th century, Emperor Susneyos could field _**“30,000 to 40,000 soldiers, 4,000 or 5,000 on horseback and the rest on foot. Of the horses up to 1,500 may be jennets of quality, some of them very handsome and strong, the rest jades and nags. Of these horsemen as many as 700 or 800 wear coats of mail and helmets.”**_[33](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-33-165941643)

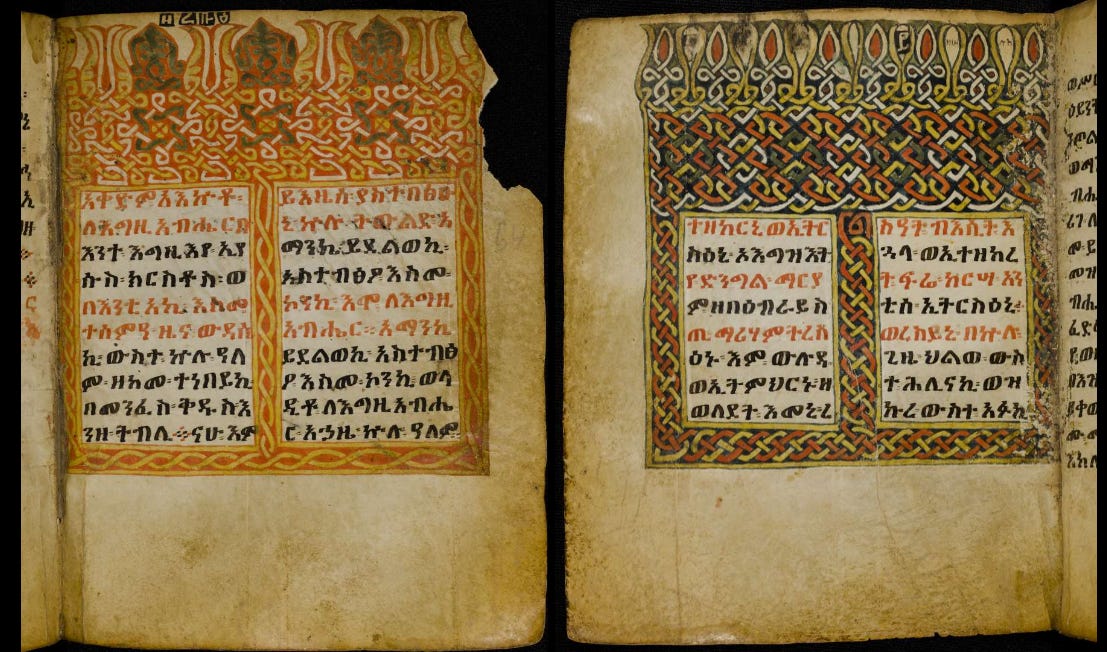

During the 18th century, the main Ethiopian army consisted of four regiments which were named after “houses” of about 2,000 men each, of which 500 were horsemen. The royal cavalry consisted of Sanqella, from the west of the capital. They wore coats-of-mail, and the faces of their horses were protected with plates of brass with sharp iron spikes, and the horses were covered with quilted cotton armor. The stirrups were of the Turkish type which held the whole foot, rather than only one or toes as was common in Ethiopia. Each rider was armed with a 14ft long lance and equipped with a small axe and a helmet made of copper or tin.[34](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-34-165941643)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_GPp!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa9ebe984-961c-4e49-ba0a-129654ac1964_1053x591.png)

(left) _**St Fasilidas on a horse covered with quilted cotton armour**_. Mural from the church of Selassie Chelekot near Mekele, Tigray, Ethiopia. image by María-José Friedlander[35](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-35-165941643)_**Quilted horse armour used by Mahdists of Sudan**_. 19th century. British Museum.

Horse equipment was mostly made by local craftsmen since the middle ages. The 14th-century monarch ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon is said to have formally organized in his court fifteen ‘houses’ each of which had its special responsibility. At least three of them looked after his defensive armor, his various other weapons of war, and the fittings of the horses.[36](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-medieval-knights-of-ethiopia#footnote-36-165941643)